Most people get vaccines without a second thought. But if you’ve heard stories about allergic reactions-especially after the COVID-19 shots-you might wonder: Is this something I need to worry about? The short answer? Almost certainly not. Vaccine allergic reactions are incredibly rare. But when they do happen, they’re taken seriously. And that’s because we have systems in place to catch them, study them, and make sure future doses are safer for everyone.

How Rare Are Allergic Reactions to Vaccines?

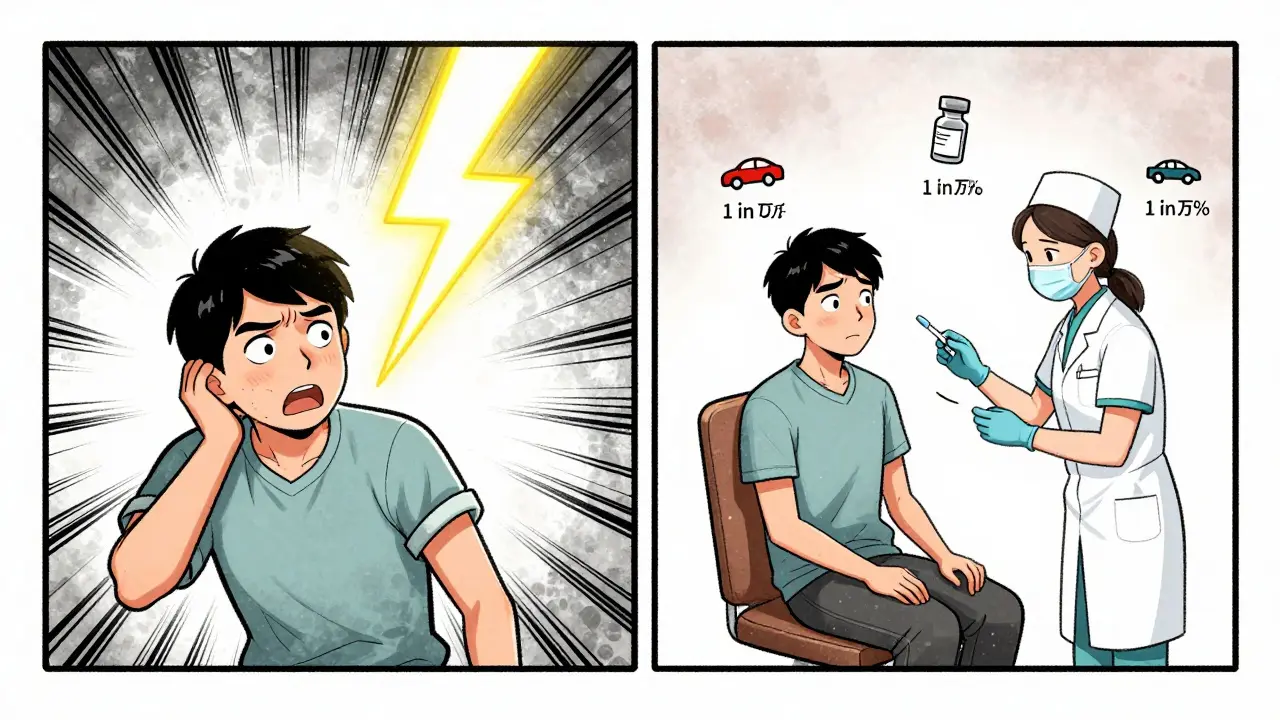

Let’s put it in perspective. Out of every million doses given, about 1 to 11 people might have a severe allergic reaction. That’s less than the chance of being struck by lightning in a given year. For most vaccines, the rate is around 1.3 cases per million. Even for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, which had slightly higher numbers early on, it was still only 5 to 11 cases per million doses. In other words, you’re far more likely to be hit by a car walking across the street than to have a serious allergic reaction to a vaccine.

Most of these reactions are anaphylaxis-sudden swelling, trouble breathing, hives, or a drop in blood pressure. And here’s the key: 86% of them happen within 30 minutes of getting the shot. More than 70% happen within the first 15 minutes. That’s why clinics ask you to wait after vaccination. It’s not just routine. It’s lifesaving.

What Causes These Reactions?

People often assume it’s the virus part of the vaccine-or the egg protein in flu shots. But that’s not usually the case. The real culprits are ingredients that help the vaccine work or stay stable. For example:

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG), found in mRNA vaccines like Pfizer and Moderna, has been linked to some anaphylaxis cases. It’s also in laxatives and cosmetics, so people with known PEG allergies are screened now.

- Polysorbate 80, used in some vaccines, is chemically similar to PEG and can trigger reactions in people allergic to it.

- Yeast proteins were once a concern with hepatitis B and HPV vaccines, but actual cases are extremely rare-only about 15 possible cases ever reported in the U.S. out of hundreds of thousands of allergic reaction reports.

- Aluminum salts, used as adjuvants in many vaccines, don’t cause anaphylaxis. Instead, they can cause long-lasting lumps at the injection site. Not dangerous, just annoying.

And what about egg allergies? You might remember being told to avoid flu shots if you were allergic to eggs. That advice changed years ago. Studies now show over 4,300 people with severe egg allergies received flu vaccines without a single serious reaction-not even a rash. The amount of egg protein in modern flu vaccines is so tiny, it’s not a threat. The CDC no longer requires special precautions for egg-allergic individuals.

Who’s at Higher Risk?

Women make up about 81% of reported allergic reactions to vaccines. The average age is around 40, but cases have been seen in kids as young as 3 months and adults up to 88. That means no one is truly immune to the possibility-but it’s still extremely unlikely.

People with a history of severe allergic reactions to anything-food, insect stings, medications-are more likely to have a reaction to a vaccine. But here’s the important part: having one allergy doesn’t mean you’ll react to a vaccine. It just means you should talk to your doctor before getting vaccinated, especially if you’ve had anaphylaxis before.

Also, about 31% of people who report a reaction had it after their first dose. That suggests they may have been sensitized to something in the vaccine before-even if they didn’t know it. That’s why doctors ask about past reactions before giving any shot.

How Are Reactions Monitored?

The U.S. has one of the most advanced vaccine safety systems in the world: VAERS-the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. It’s run by the CDC and FDA. Anyone-doctors, patients, parents-can report a reaction. It’s not perfect. Reports can be incomplete, or even unrelated to the vaccine. But it’s a powerful early warning system.

Every year, VAERS gets 30,000 to 50,000 reports. Less than 1% are serious allergic reactions. When something unusual pops up-like a spike in a certain type of reaction-scientists dig in. They cross-check with other databases, like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which tracks millions of medical records. That’s how they confirmed the slight increase in anaphylaxis with mRNA vaccines-and also confirmed it was still extremely rare.

Other countries have similar systems. The European Medicines Agency runs EudraVigilance, which handles over a million reports annually. The World Health Organization works with 137 countries to keep global standards high.

What Happens If You Have a Reaction?

All vaccination sites are required to have epinephrine on hand. That’s the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis. Staff are trained to recognize symptoms fast. If you start to feel dizzy, break out in hives, or have trouble breathing after a shot, tell them immediately. They’ll give you epinephrine, monitor your vitals, and call for emergency help if needed.

Afterward, you’ll be asked to fill out a report. Even if you feel fine, if you had a reaction, it needs to go into VAERS. That’s how we learn. You’re not just protecting yourself-you’re helping protect others.

If you’ve had a confirmed anaphylaxis reaction to a vaccine, you’ll be referred to an allergist. They’ll test to find out what caused it-PEG? Polysorbate? Something else? Then they’ll help you decide if future vaccines are safe, and how to get them safely. In most cases, people can still get future doses, just under supervision and sometimes with different brands.

What About Long-Term Risks?

There’s no evidence that vaccines cause long-term allergic problems. The only lasting effect might be a small, painless lump at the injection site if aluminum was used. That can last weeks or months, but it’s harmless.

Some people worry about autoimmune reactions like Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). That happened after the 1976 swine flu vaccine, and it’s why we have monitoring systems today. Since then, GBS has been linked to vaccines only in rare, isolated cases-far less than the risk from getting the actual disease. For example, the flu itself is much more likely to trigger GBS than the flu shot.

Researchers are now looking for biomarkers-tiny signals in the body-that might predict who’s at risk before they even get the shot. Early studies are promising. In the next 5 to 7 years, we might have simple blood or skin tests to screen for PEG or polysorbate sensitivity. That could make vaccination even safer.

Why This Matters

Public fear around vaccine allergies is one of the top reasons people delay or skip shots. The CDC says about 12% of vaccine hesitancy is tied to fear of allergic reactions. But the data tells a different story. The risk of dying from measles, flu, or COVID-19 is thousands of times higher than the risk of dying from a vaccine reaction.

Every time we vaccinate, we’re not just protecting one person. We’re protecting communities. And the systems that monitor reactions-VAERS, v-safe, EudraVigilance-are what make that possible. They’re not perfect, but they’re the best we’ve ever had. And they’re getting better.

If you’ve had a reaction before, talk to your doctor. Don’t assume you can’t be vaccinated. If you’re nervous, ask about the ingredients. Most vaccines don’t contain egg, yeast, or latex anymore. And if you’re healthy and have no history of severe allergies? You’re almost certainly fine.

Vaccines are one of the safest medical tools we have. The fear around them is out of proportion to the risk. The science is clear. The monitoring is strong. And the protection they offer? Irreplaceable.

Can you have an allergic reaction to a vaccine you’ve had before without problems?

Yes, but it’s rare. Some people develop sensitivity over time, especially to ingredients like PEG or polysorbate. If you had no reaction to your first dose of a vaccine but had one on the second, it’s worth seeing an allergist. They can help determine if it’s a true allergy or a coincidence.

Should I avoid vaccines if I’m allergic to peanuts or shellfish?

No. Food allergies like peanuts or shellfish are not linked to vaccine ingredients. There’s no cross-reactivity. You can safely get any vaccine, including mRNA shots, even if you’ve had anaphylaxis to food. The only exceptions are if you’re allergic to PEG, polysorbate, or another specific vaccine component.

Is it safe to get vaccinated if I have a history of anaphylaxis from something else?

Yes, but you should be monitored for 30 minutes after vaccination. Your provider may recommend getting the shot in a medical setting where emergency care is immediately available. You don’t need to avoid vaccines-you just need to be cautious.

Do vaccines contain gelatin or latex?

Some older vaccines used gelatin as a stabilizer, and a few vaccine vial stoppers contained latex. Most modern vaccines no longer use these ingredients. If you’re allergic to gelatin or latex, ask your provider to check the vaccine’s ingredient list. They can usually find a suitable alternative.

What should I do if I think I had an allergic reaction to a vaccine?

Seek medical care immediately if you’re having symptoms like trouble breathing, swelling, or dizziness. Afterward, report it to VAERS-even if you’re not sure it was the vaccine. Your report helps improve safety for everyone. You can file a report online at vaers.hhs.gov or ask your doctor to do it for you.