If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and seen a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward your pupil, you’re not alone. This isn’t a scratch, an infection, or a random bump - it’s pterygium, commonly called "Surfer’s Eye." It’s not cancer. It won’t spread. But if left unchecked, it can blur your vision, make contact lenses unbearable, and leave your eye looking red and irritated for years. And the biggest cause? Sunlight - specifically, the UV rays you’re exposed to every day, even on cloudy days.

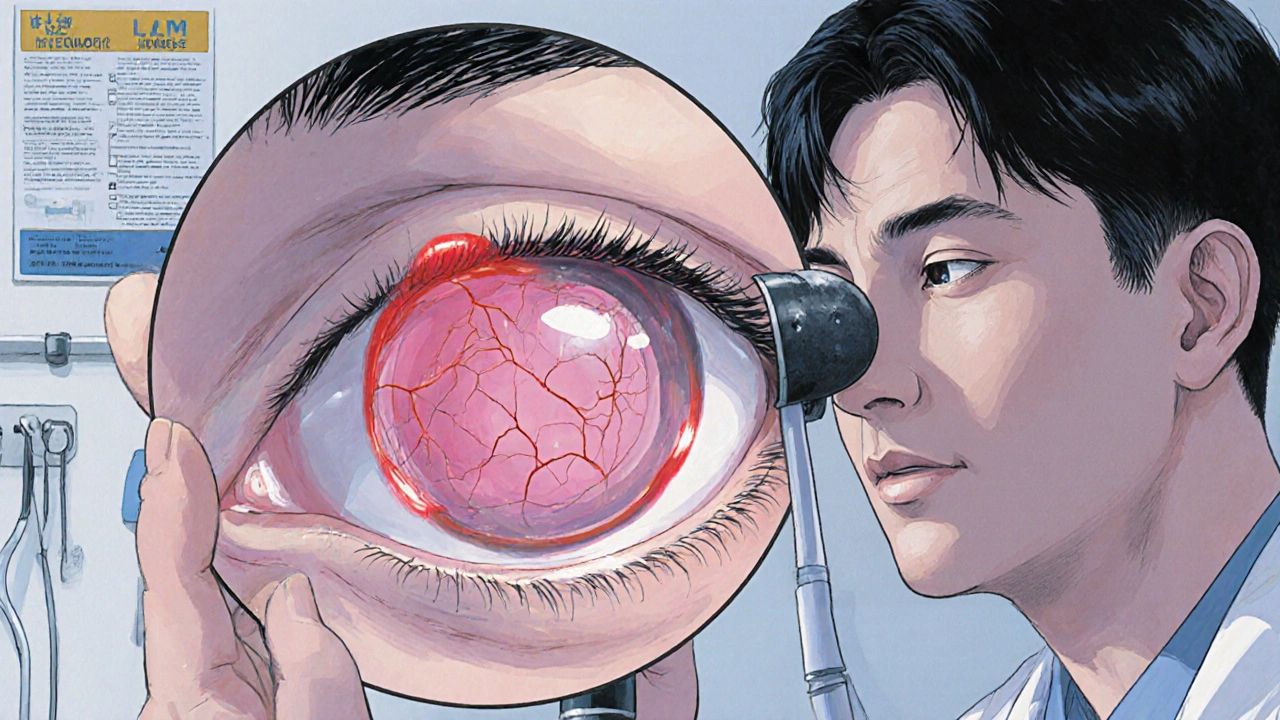

What Exactly Is Pterygium?

Pterygium is a growth of the conjunctiva - the thin, clear tissue that covers the white part of your eye. It starts near the nose, grows slowly across the sclera (the white), and can creep onto the cornea (the clear front surface of your eye). When it reaches the cornea, it can change its shape, causing astigmatism and blurry vision. It looks like a wing-shaped flap of tissue, often pink or red with visible tiny blood vessels. In Australia, where UV levels are among the highest in the world, about 12% of men over 60 have it. In places closer to the equator, like Queensland or northern Brazil, that number can jump to 20% or higher.

It’s not the same as a pinguecula - a yellowish bump on the white of the eye that stays on the conjunctiva and never reaches the cornea. A pinguecula is more common, affecting up to 70% of outdoor workers in tropical areas. But when that bump starts growing toward the pupil, it becomes a pterygium. That’s when it starts to matter.

Why Does the Sun Cause It?

The link between UV light and pterygium isn’t just a theory - it’s backed by decades of research. A study from the University of Melbourne found that people who’ve been exposed to more than 15,000 joules of UV radiation per square meter over their lifetime have a 78% higher chance of developing pterygium. That’s roughly the amount you’d get from spending 30 minutes outside every day for 20 years without eye protection.

It’s not just beach days or surfing. It’s your morning commute, your lunch break outside, your weekend gardening, your kids’ soccer games. UV rays bounce off water, sand, snow, and even concrete. In Melbourne, the UV index hits 3 or above on more than 200 days a year - enough to damage your eyes. And if you’re male, you’re more likely to get it. Studies show a 3:2 male-to-female ratio, likely because men spend more time outdoors in jobs like construction, farming, or fishing.

Genetics might play a small role - some families have more cases - but environmental exposure is the main driver. If you’ve got pterygium, it’s almost certainly because of how much sun your eyes have taken over the years.

How Do You Know If It’s Getting Worse?

Early-stage pterygium might not bother you at all. You might just notice a bit of redness or a small bump. But as it grows, symptoms become harder to ignore:

- Chronic redness or irritation

- Feeling like there’s grit or sand in your eye

- Difficulty wearing contact lenses

- Blurred or distorted vision - especially if the growth is near your pupil

- Visible change in the shape of your eye

Doctors diagnose it with a simple slit-lamp exam - a bright, magnified light that lets them see exactly how far the growth has traveled onto your cornea. No blood tests, no scans. Just a quick look. If it’s only 1-2 millimeters wide and hasn’t reached your pupil, it’s considered mild. If it’s over 3 millimeters and crossing into your line of sight, treatment becomes necessary.

Can You Stop It From Growing?

Yes - if you act early. The single most effective way to stop pterygium from getting worse is to block UV light. That means:

- Wearing sunglasses that block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays (look for ANSI Z80.3-2020 certification)

- Choosing wraparound styles that shield your eyes from side exposure

- Wearing a wide-brimmed hat every time you’re outside

- Avoiding peak sun hours (10 a.m. to 4 p.m.) when UV levels are highest

Patients who follow this advice report that their pterygium stops growing. One Reddit user, "OutdoorPhotog," said his annual eye exams showed no progression after he started wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily. That’s not luck - it’s science.

Over-the-counter lubricating eye drops can help with dryness and irritation, but they won’t shrink the growth. Prescription steroid drops may reduce redness temporarily, but long-term use isn’t safe. Prevention isn’t optional - it’s the only non-surgical solution that works.

When Is Surgery Necessary?

Surgery isn’t needed for every pterygium. Most people never need it. But if your vision is blurry, your eye is constantly irritated, or the growth is cosmetically disturbing, it’s time to talk to an ophthalmologist.

The most common procedure is called a conjunctival autograft. Here’s how it works:

- The pterygium is carefully peeled off the cornea and sclera.

- A small piece of healthy conjunctiva is taken from under your upper eyelid.

- That graft is stitched or glued over the area where the pterygium was removed.

This isn’t just about removing the growth - it’s about replacing the damaged tissue with healthy tissue to prevent it from coming back. Without a graft, recurrence rates are 30-40%. With a graft, they drop to under 10%.

Some surgeons also use a drug called mitomycin C during surgery. It’s a mild chemotherapy agent applied briefly to the eye surface to kill off the cells that cause regrowth. When used with a graft, recurrence rates fall even further - to about 5%.

Another newer option is amniotic membrane transplantation, where tissue from a donated placenta is used to cover the eye. It’s especially helpful for recurrent pterygium and has shown 92% success in preventing regrowth in European trials.

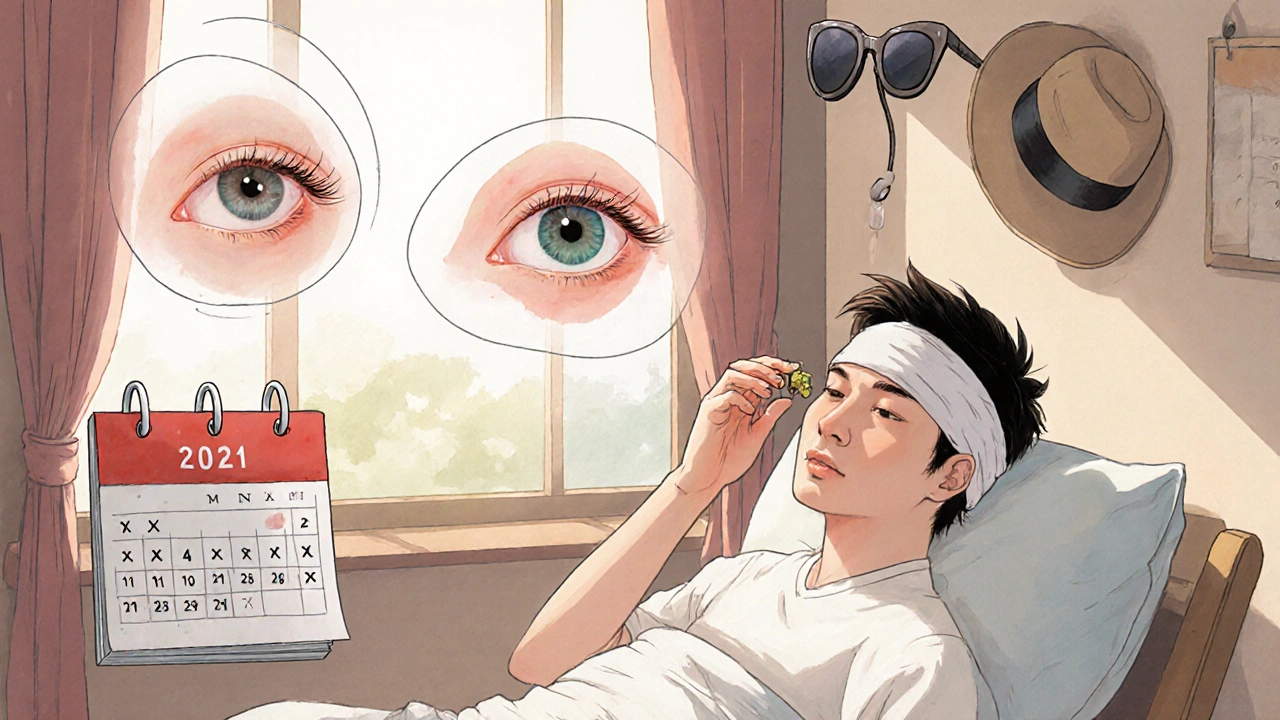

What’s Recovery Like?

Surgery takes about 30-45 minutes and is done under local anesthesia. You’re awake but feel no pain. Most people go home the same day.

Recovery isn’t glamorous:

- Your eye will be red and swollen for 1-2 weeks

- You’ll need steroid eye drops for 4-6 weeks to reduce inflammation

- You can’t swim, use makeup, or rub your eye for at least 4 weeks

- Some people feel a scratchy sensation for up to 3 weeks

But the results? Most patients report immediate relief from irritation. Vision improves as the cornea returns to its normal shape. A survey of over 1,200 patients found 87% were happy with the outcome. The biggest complaint? The steroid drops. One patient on RealSelf.com said, "The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected."

What Happens If You Don’t Treat It?

Some pterygia stay small and harmless for life. But others keep growing. If it reaches the center of your cornea, it can permanently distort your vision. You might need new glasses or contacts every year. In extreme cases, it can block light from entering your eye, causing noticeable vision loss.

And if you wait too long, surgery becomes more complicated. Large pterygia can scar the cornea, making it harder to restore clear vision even after removal. The longer you wait, the higher the chance of permanent damage.

What’s New in Pterygium Treatment?

Research is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved OcuGel Plus, a preservative-free lubricant designed specifically for post-surgery patients. It reduced discomfort by 32% compared to standard eye drops.

There’s also exciting work on topical rapamycin, a drug that blocks the cells responsible for regrowth. In Phase II trials, it cut recurrence rates by 67% compared to placebo. If approved, it could become a daily eye drop alternative to surgery.

By 2027, 78% of eye surgeons expect to use laser-assisted removal - a technique that’s faster, more precise, and causes less trauma to surrounding tissue.

Final Thoughts: Protect Your Eyes - Now

Pterygium isn’t an emergency. But it’s a warning sign. If you spend time outdoors - and especially if you live in Australia, South Africa, India, or any region near the equator - your eyes are taking damage every day. The good news? You can stop it. Sunglasses aren’t fashion. They’re medical equipment. A hat isn’t optional. It’s your first line of defense.

If you already have a pterygium, don’t panic. See an eye doctor. Get it measured. Know how far it’s grown. And if it’s starting to affect your vision, don’t wait. Surgery is safe, effective, and often life-changing.

It’s not about avoiding the sun. It’s about protecting your eyes while you enjoy it.

Can pterygium go away on its own?

No, pterygium does not go away on its own. Once it forms, it may stay stable, but it won’t shrink or disappear without treatment. Some small cases stop growing if UV exposure is reduced, but the tissue remains. Surgery is the only way to remove it completely.

Are sunglasses enough to prevent pterygium?

Sunglasses are the most effective prevention tool - but only if they block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays and fit close to your face. Wraparound styles work best. Regular sunglasses without full UV protection won’t help. Combine them with a wide-brimmed hat for maximum defense.

Is pterygium surgery painful?

The surgery itself is not painful - local anesthesia numbs the eye. Afterward, you’ll feel some discomfort, like having sand in your eye, for a few days. Most people manage it with over-the-counter pain relievers. The real challenge is the 4-6 weeks of steroid eye drops, which can cause temporary pressure changes or irritation.

Can pterygium come back after surgery?

Yes, but not if you do it right. Without a graft or mitomycin C, recurrence rates are 30-40%. With a conjunctival autograft and mitomycin C, recurrence drops to 5-10%. The biggest risk factor for regrowth? Going back into the sun without eye protection.

Is pterygium more common in certain countries?

Yes. Countries within 30 degrees of the equator have the highest rates - Australia, Brazil, India, Mexico, and parts of Africa. Australia has the highest national prevalence at 23% among adults over 40, largely due to high UV levels and outdoor lifestyles. People in urban areas with access to eye care are diagnosed earlier than those in rural or developing regions.

Can children get pterygium?

It’s rare, but possible. Children who spend long hours outdoors without eye protection - especially in sunny climates - can develop early signs. The condition usually takes years to grow, so it’s more common in adults over 40. But protecting kids’ eyes from UV exposure from an early age can prevent it later in life.

Erika Lukacs

November 16, 2025 AT 17:19It's wild how something so simple-sunlight-can quietly wreck your vision over decades. We protect our skin, but our eyes? We treat them like they're invincible. Maybe we should start thinking of sunglasses like seatbelts: not optional, just basic survival gear.

Rebekah Kryger

November 18, 2025 AT 13:40Let’s be real-this whole 'Surfer’s Eye' thing is just capitalism repackaging environmental neglect as a personal failure. If the government subsidized UV-blocking eyewear like they do insulin, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. Instead, we get influencer sunglasses that block 40% of UV and call it a day.

Victoria Short

November 19, 2025 AT 00:58I have one. Doesn’t bother me. Just looks weird. Wore shades once, forgot about it. Still here. Probably gonna be here till I die.

Eric Gregorich

November 20, 2025 AT 17:23Think about it-human beings evolved under a sun that didn’t have ozone depletion, didn’t have reflective urban surfaces, didn’t have 12-hour workdays spent staring at screens while walking to the bus stop under a sky that’s basically a UV sieve. We’re not designed for this. Our eyes are ancient organs in a modern hellscape. The pterygium isn’t a disease-it’s a protest. A biological scream from a tissue that’s been screaming for decades and finally grew a wing to get your attention. And what’s our solution? More drops? More surgery? Or do we finally stop pretending we can out-engineer evolution with a $20 pair of polarized plastic? We need systemic change, not just eye drops. We need cities designed for shade. We need public health campaigns that don’t treat eye protection like a lifestyle accessory. This isn’t about you being lazy-it’s about the world being negligent.

Koltin Hammer

November 21, 2025 AT 03:10Been living in Arizona for 18 years. My dad had pterygium. I got mine at 32. Wore cheap sunglasses until I was 30. Then I bought the $150 wraparounds with the ANSI stamp. No more redness. No more grit feeling. My optometrist says it’s stabilized. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the cheapest insurance policy you’ll ever buy. And honestly? They look cool. Like you’re a secret agent who just got back from a desert mission.

Phil Best

November 21, 2025 AT 23:34Let me get this straight-you’re telling me I need to wear a hat AND sunglasses AND avoid the sun between 10 and 4… just so my eye doesn’t turn into a creepy little alien wing? And if I don’t, I might need surgery where they rip tissue out of my eyelid and glue it back on? Bro. I just want to walk my dog at 5 p.m. without looking like a deranged beach bum. This is the most dramatic eye disease I’ve ever heard of. Next you’ll tell me my cornea is gonna start humming the theme to Jaws.

Parv Trivedi

November 23, 2025 AT 23:19In India, we call it "surfer's eye" too-even though most of us don’t surf. My uncle, a farmer in Bihar, had it badly. He never wore a hat or glasses. By 60, his vision was blurry. Surgery helped, but only because he finally listened. The real tragedy? Many don’t even know what it is. We need more awareness in rural clinics. A simple pamphlet, a poster in the local shop-these things save sight. It’s not expensive. It’s just not prioritized.

Willie Randle

November 25, 2025 AT 09:51Important clarification: UV exposure is cumulative. Every minute counts-even on cloudy days. UVA penetrates cloud cover. Reflection off concrete can increase exposure by up to 25%. And no, "tinted lenses" don’t equal UV protection. Always check the label. ANSI Z80.3-2020 is the standard. If it doesn’t say that, it’s not reliable. Also, children’s lenses are more transparent to UV than adults’. Start early. Don’t wait for symptoms.

Connor Moizer

November 27, 2025 AT 01:39You people are acting like this is some rare medical mystery. It’s not. It’s a fucking warning sign that you’re a lazy ass who refuses to wear sunglasses. I’ve seen guys in their 20s with this because they think "sunglasses make me look like a dork." Guess what? Looking like a dork with 20/20 vision beats looking like a deranged owl with a corneal scar. Get your act together. Stop being a coward. Protect your eyes or pay the price later.

kanishetti anusha

November 28, 2025 AT 22:57I’m from Kerala, India. We have sun all year. My mother had pterygium. She used to say, "It’s just a little redness, it’ll go away." It didn’t. After surgery, she said the steroid drops were worse than the growth. But now she wears her hat every morning, even to the market. I started wearing my sunglasses at 19. I’m 28 now. No sign of anything. It’s not hard. Just consistent.

roy bradfield

November 30, 2025 AT 04:35This whole thing is a Big Pharma scam. They don’t want you to know that pterygium is caused by fluoride in the water and 5G radiation from cell towers. The surgery? A cover-up. They remove the growth, then sell you steroid drops to keep you dependent. The real cure? Detox your body with Himalayan salt and infrared saunas. I’ve seen it happen. My cousin’s pterygium vanished after he stopped using WiFi and started sleeping under a copper pyramid. The medical industry hates this truth. They’re terrified of natural solutions.

Patrick Merk

November 30, 2025 AT 14:32My granddad had pterygium in Donegal. Used to say, "It’s just the Irish sun, lad." He wore a cap and never bothered with sunglasses. Lived to 89. Vision was fine till the end. Maybe it’s not all about UV? Maybe genetics, or even wind and salt spray? I’m not saying skip protection-but maybe we’re oversimplifying. The eye’s a complex little machine. We don’t always have all the answers.

Liam Dunne

December 1, 2025 AT 12:27Just had the autograft last month. Recovery was rough-3 weeks of steroid drops, no makeup, no swimming, no rubbing (I rubbed once. Regretted it for 48 hours). But the difference? Night and day. No more redness. No more grit. My vision’s sharper. And the best part? My optometrist says it’s unlikely to come back. I wear my shades like they’re part of my face now. And I bought my kid a pair too. No excuses.