Why Generic Drugs Don’t Hit the Market at the Same Time Everywhere

You might think that once a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, any company can start making the cheaper version. But that’s not how it works. The timing of when a generic drug becomes available depends on where you live. In the U.S., a generic might show up months after patent expiration. In Europe, it could take years longer. And in some low-income countries, patients may wait over a decade. This isn’t random-it’s built into the law.

The core idea behind drug patents is simple: reward innovation. Developing a new medicine costs about $2.3 billion on average, according to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. Companies need time to recoup that investment before competitors copy the formula. But once that protection ends, generics should step in to lower prices. The problem? The rules for when generics can enter vary wildly across countries-and many of them are designed to delay competition, not speed it up.

Patent Length Is Global, But Protection Isn’t

Under the TRIPS Agreement from 1995, all member countries must grant drug patents for 20 years from the date the patent is filed. That sounds fair. But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 12 years just to get approved by regulators. That means by the time a drug hits the market, there’s often only 6 to 10 years of patent life left. To make up for lost time, countries have created extra protections.

In the U.S., the FDA allows Patent Term Extension (PTE), which can add up to five years to a patent-but only if the total protection after extension doesn’t go beyond 14 years after the drug is approved. For example, if a drug got approved in 2015 and had 7 years of patent life left, it could get extended to 14 years post-approval. That means the drug stays protected until 2029, even if the original patent expired in 2025.

The EU does something similar with Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). These can add up to five years of protection, but the combined patent and SPC time can’t exceed 15 years from the drug’s first marketing authorization. So even if two drugs have the same patent filing date, their real market exclusivity can be completely different depending on when they got approved.

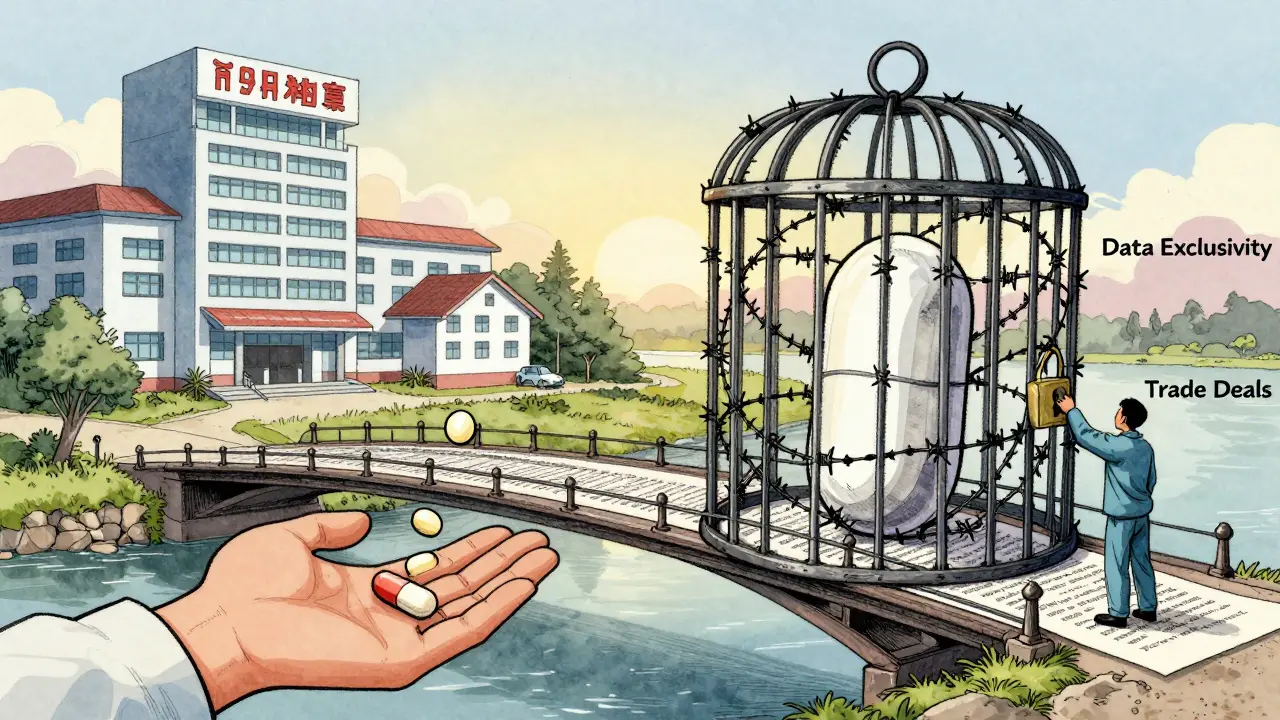

More Than Patents: Data Exclusivity Is the Real Barrier

Even if a patent expires, generics still can’t always launch right away. That’s because of something called data exclusivity. This isn’t about patents-it’s about the clinical trial data the original company spent millions generating. Regulators can’t approve a generic based on that data until a certain period has passed.

In the U.S., a new chemical entity gets 5 years of data exclusivity. During that time, the FDA can’t rely on the brand-name company’s clinical trials to approve a generic. But here’s the twist: if the generic maker does its own studies, it can bypass this. That rarely happens because it’s expensive and time-consuming.

Europe’s system is stricter. It uses an 8+2+1 model: 8 years of data exclusivity, then 2 years where generics can’t even apply for approval, and a possible 1-year extension if the drug shows major clinical benefits. That means a new drug could be protected for up to 11 years without a single patent being enforced. Canada follows a similar 8+2 model. Japan gives 8 years of data protection and 4 years of market exclusivity.

These rules matter because most generic manufacturers don’t run new trials. They rely on the original data. So if the data is locked up, the generic can’t get approved-even if the patent is gone.

The U.S. Has a Secret Weapon: The 180-Day Exclusivity Trick

One of the most powerful-and controversial-tools in the U.S. system is the 180-day exclusivity period for the first generic company that successfully challenges a patent. This is part of the Hatch-Waxman Act from 1984. If a generic maker files a Paragraph IV certification (saying the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed), and wins in court, they get six months of exclusive rights to sell their version. No other generic can enter until that period ends.

This sounds great for competition. But in practice, it’s often used as a bargaining chip. Brand-name companies sometimes pay the first generic maker to delay launch. These “pay-for-delay” deals were ruled illegal in 2013 by the Supreme Court in FTC v. Actavis, but they still happen. A 2023 American Pharmacists Association survey found that 78% of pharmacists saw delays in generic availability because of these settlements.

And it’s not just about one company. Sometimes, multiple generics file challenges, but only the first one gets the 180-day window. That creates a race to the courthouse-and a legal minefield. The average brand-name drug now has 142 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, according to Teva’s CEO. Challenging them all costs $2 to $5 million per drug.

How Other Countries Compare

Outside the U.S. and EU, the rules get even more uneven.

China extended its data exclusivity from 6 to 12 years in 2020. Brazil introduced 10 years in 2021. These moves mirror the U.S. and EU, but they’re happening in countries where medicines are already unaffordable for most people.

In contrast, India and South Africa still follow a looser interpretation of TRIPS. They allow generic production as soon as patents expire, even if data exclusivity hasn’t ended. But trade deals like CETA (Canada-EU) and others have pushed countries to adopt stricter rules. Dr. Ellen ‘t Hoen, an access-to-medicines expert, says these agreements have delayed HIV drug generics in South Africa by up to 11 years after patent expiry.

Low-income countries face another hurdle: they often lack the regulatory capacity to review generic applications quickly. Even when patents expire, it can take years for local agencies to approve generics. The WHO found that essential medicines reach generic status in high-income countries after 12.7 years on average-but 19.3 years in low-income ones.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

Originator companies clearly win. Merck reported that its cancer drug Keytruda’s effective exclusivity stretched from 8.2 years to 12.7 years thanks to patent stacking and exclusivity extensions. That’s over four extra years of monopoly pricing.

Generic manufacturers win too-but only if they can afford the legal battles. The top 10 generic makers now control 65% of the U.S. market, according to Evaluate Pharma. Smaller companies can’t compete. Many just give up.

Patients lose the most. When exclusivity is extended, prices stay high. The average price drop after generic entry is 80-90% within a year, per IQVIA. That’s billions in savings lost. For a drug like EpiPen, where the brand version cost $600 for two pens, a generic could have brought it down to $150. But patent challenges and delays kept the price high for years.

And it’s not just about money. Orphan drugs-medicines for rare diseases-get 7 years of exclusivity in the U.S. and 10 in the EU. That’s led to 12 new treatments for multiple myeloma since 2003, according to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation. But for common conditions like hypertension or diabetes, the same system creates artificial scarcity.

What’s Changing? And What’s Not

Pressure is building. The U.S. Congress reintroduced the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act in 2023 to ban pay-for-delay deals. The EU is proposing to cut data exclusivity to 5 years for some drugs. Japan plans to speed up its patent review process.

But the big players aren’t backing down. PhRMA says without strong protections, innovation would collapse. And with 14% of drugs failing in Phase III trials, they argue the system is necessary.

Still, the numbers tell a different story. The World Health Organization says most drugs don’t need 12 years of exclusivity. R&D costs for common medicines are far lower than the $2.3 billion average. And 97% of originator companies say current rules are “essential”-but that’s the same group that files an average of 137 patents per drug, according to LexisNexis PatentSight.

The truth? The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed-for companies, not patients. The real question isn’t whether exclusivity should exist. It’s how long it should last, and who it’s really protecting.

How Long Do You Really Have to Wait?

Here’s a quick snapshot of how long generics typically wait after a drug’s first approval:

- United States: 5-12 years (depending on data exclusivity, patent extensions, and legal challenges)

- European Union: 8-11 years (8+2+1 structure)

- Canada: 8-10 years (8+2 model)

- Japan: 8-12 years (8+4 model)

- China: 10-12 years (since 2020)

- Brazil: 10 years (since 2021)

- India: As soon as patent expires (no data exclusivity)

- Low-income countries: 15-20+ years (due to regulatory delays and trade pressures)

That’s not just a delay. It’s a global inequality in access to medicine.

What’s Next?

By 2027, patent term extensions will make up 45% of total market exclusivity, up from 32% in 2020, according to McKinsey. That means even more drugs will be locked up longer. The $356 billion in branded sales set to lose patent protection between 2023 and 2028 will be fiercely defended.

Patients and taxpayers will foot the bill. Pharmacists will keep seeing delays. And generic companies will keep spending millions just to get into the game.

There’s no easy fix. But if the goal is affordable medicine, then the rules need to change. Not to kill innovation-but to stop it from becoming a tool for profit at the cost of health.

Russ Kelemen

January 29, 2026 AT 22:20It’s wild how the system is engineered to keep prices high under the guise of ‘innovation.’ I get that R&D costs are insane, but when a company files 140+ patents on one drug just to stretch exclusivity, that’s not innovation-that’s legal gymnastics. The real innovation should be in making medicine accessible, not in finding loopholes to keep people paying $600 for an EpiPen.

I’ve worked in pharmacy for 18 years. I’ve seen patients skip doses because they can’t afford the brand, then end up in the ER. That’s not a health outcome-that’s a policy failure.

Sidhanth SY

January 31, 2026 AT 12:58India’s been the unsung hero of global access. We don’t play the patent game the same way-patents expire, generics launch. Simple. And yeah, we’ve gotten pressure from trade deals, but we’ve still kept life-saving HIV and hepatitis drugs affordable for millions. If the U.S. and EU really cared about global health, they’d stop pushing their exclusivity rules on developing nations.

It’s not about stealing innovation. It’s about survival. When your kid needs insulin and the only option costs 10x your monthly salary, you don’t care about a CEO’s bonus-you care about living.