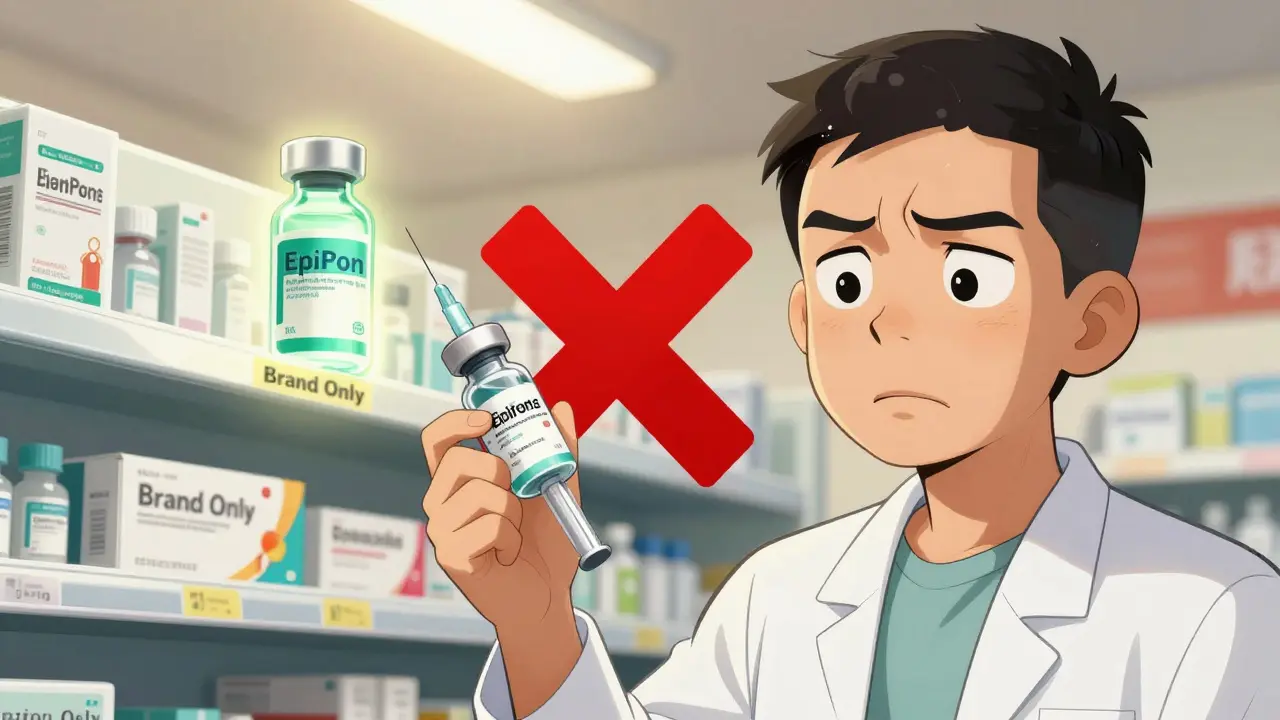

Imagine you need an EpiPen. Your doctor prescribes it. You go to the pharmacy and get a generic version - but it’s not the same. You get a vial of epinephrine and a separate auto-injector that doesn’t fit. Or worse, you get the right device, but the drug inside isn’t approved to work with it. This isn’t a glitch. It’s the reality of generic combination products.

Most people think generics are simple: same drug, cheaper price. But when a product combines a drug with a device - like an inhaler, auto-injector, or prefilled syringe - the rules change. You can’t just swap out the drug. You need the right device too. And if the generic device doesn’t exist, or isn’t approved to work with the generic drug, you’re stuck paying full price for the brand.

What Exactly Is a Combination Product?

A combination product isn’t just two things in one box. It’s a single medical product made of two or more parts that work together to treat a condition. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines it as something where: the drug and device are physically combined, packaged together, or labeled specifically to be used as a pair.

Think about these common examples:

- An EpiPen - epinephrine drug + auto-injector device

- An asthma inhaler - albuterol drug + metered-dose device

- A prefilled insulin pen - insulin drug + spring-loaded injector

These aren’t just drugs in devices. They’re systems. The device isn’t a container - it’s part of the treatment. If the device doesn’t deliver the drug correctly, the whole thing fails. That’s why the FDA treats them as one product, not two.

Why Can’t You Just Swap the Drug?

Here’s where things get messy. In the U.S., state laws allow pharmacists to substitute generic drugs for brand-name ones - as long as they’re bioequivalent. That works fine for pills. But for combination products, it doesn’t apply.

Why? Because the device matters. A generic epinephrine vial might be chemically identical to the brand. But if the auto-injector it’s meant to go with isn’t approved as a generic, the FDA won’t allow substitution. The device has to be tested for:

- How well it delivers the dose

- How easy it is for patients to use

- Whether it matches the original in feel, sound, and timing

This is called human factors engineering. It’s not just about chemistry - it’s about how real people interact with the product under stress. A patient having an allergic reaction doesn’t have time to figure out a new device. If the button feels different, the click sounds off, or the needle doesn’t pop out at the right depth, it could be life-threatening.

So even if you have a generic drug and a generic device, they might not be approved to work together. That’s the gap: multiple generics equaling one brand isn’t legally or technically allowed - yet.

The Regulatory Maze

The FDA has a special office for these products: the Office of Combination Products. It decides whether the drug or the device is the main reason the product works - called the Primary Mode of Action (PMOA). That determines which team reviews it: drug experts, device experts, or both.

For a generic version to get approved, the manufacturer must prove:

- The drug is identical to the brand’s

- The device is functionally the same

- Together, they perform the same way

That last part is the killer. It’s not enough to test the drug alone or the device alone. You need to test the whole system. And that takes time - 18 to 24 months longer than a regular generic. It costs $2 million to $3.7 million extra. And 43% of applications get rejected in the first round because the device comparison wasn’t good enough.

Compare that to regular generics: 92% get approved within 10 months. For combination products? Only 47% do.

Who’s Affected? Real People, Real Costs

This isn’t just a regulatory headache. It hits patients in the wallet and the health.

Patients on PatientsLikeMe report paying 37% more out-of-pocket for complex combination products than for regular generics. One Reddit user wrote: “I can’t get a generic EpiPen because the device isn’t approved. So I pay $500 every six months. My insurance won’t cover the brand unless I prove I can’t afford the generic - but there is no generic.”

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. A 2024 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% have seen patients confused about substitution. 42% get at least one complaint per month.

Doctors see delays too. The American Medical Association found that 57% of providers have had treatment held up because the right combination wasn’t available. On average, patients wait 3.2 business days longer than they should.

And it’s getting worse. Patient advocacy groups documented 217 cases in 2023 where people couldn’t get therapeutic equivalents - a 29% jump from the year before.

Why Are So Few Generic Combination Products Available?

Only 17 companies make most of the approved generic combination products. In the regular generic market, over 120 companies compete. Why the gap?

- High cost and long timelines scare off small manufacturers

- Unclear FDA guidance makes it risky to invest

- Only 12% of manufacturers say FDA’s guidance documents are helpful

Market data shows branded combination products still hold 68% of the market. Generics? Just 12%. That’s a huge gap for a $138 billion industry.

Some areas are doing better. Inhalers for asthma have 38% generic penetration. Auto-injectors? Only 19%. Why? Because inhalers are easier to copy. The device is simpler. The drug delivery is more predictable.

Is Anything Changing?

Yes - slowly.

In April 2024, the FDA released new guidance to clarify how to prove device comparability. It’s the first time they’ve spelled out exactly what data is needed for the human factors part.

Thirteen states have introduced bills to update substitution laws. California and Massachusetts are leading the charge, trying to let pharmacists substitute combinations if both parts are generic and approved together.

The FDA launched “Complex Generic Initiative 2.0” in June 2024. Goal: cut approval times by 30% by 2026. They’ve hired 32 new reviewers just for these products - up 45% since 2022.

Analysts predict generic penetration could rise from 12% to 35% by 2027. But that’s still far from where it should be. And even then, “multiple generics equaling one brand” will still be the exception - not the rule.

What This Means for You

If you’re on a combination product:

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the only generic version approved to work together?”

- Don’t assume a generic drug and a generic device can be mixed - they might not be approved as a pair.

- If you’re paying more than you should, ask your doctor for a prior authorization letter for the brand - many insurers will cover it if no generic combo exists.

- Check the FDA’s website for approved combination generics. Not all are listed in pharmacy systems.

If you’re a prescriber:

- Write prescriptions clearly: “Do not substitute” if no approved generic combo exists.

- Know which products have true generic equivalents - and which don’t.

- Document substitution issues. Your reports help push policy change.

This isn’t about drugs or devices. It’s about access. The system was built for pills and syringes. Now it’s being asked to handle complex, life-saving tools - and it’s not ready.

Can a pharmacist substitute a generic drug for a branded combination product?

No, not automatically. Even if the drug component is generic, the device must also be approved as a generic and proven to work with that specific drug. Most combination products don’t have approved generic versions for both parts, so substitution is not allowed under current laws.

Why are generic combination products so expensive?

They’re expensive because developing them is complex and costly. Manufacturers must test both the drug and device together, including human factors studies that simulate real-world use. This adds $2-$3.7 million and 9-15 months to development. Few companies can afford it, so competition stays low and prices stay high.

What’s the difference between a generic drug and a generic combination product?

A generic drug replaces just the active ingredient in a brand-name pill or injection. A generic combination product replaces both the drug and the device - like the injector, inhaler, or pen - and must prove they work together exactly like the original. That’s why it’s harder to approve and much rarer.

Are there any generic combination products available right now?

Yes, but very few. Some asthma inhalers and insulin pens have generic versions where both the drug and device are approved together. Auto-injectors like EpiPens still mostly rely on the brand. The FDA has approved fewer than 50 true generic combination products since 2010, compared to over 10,000 regular generics.

Will this change in the next few years?

Possibly. The FDA is pushing to speed up approvals, and several states are updating laws to allow substitution if both parts are generic. But progress is slow. Even with new rules, it will take years for enough manufacturers to enter the market. Real change won’t happen until the cost and complexity drop significantly.

If you’re using a combination product, don’t assume generics are interchangeable. Ask questions. Push for clarity. And know: you’re not alone - thousands are in the same boat. The system isn’t broken. It’s just outdated. And it’s finally starting to catch up.

Pankaj Singh

January 14, 2026 AT 11:17This is a complete farce. The FDA is a bureaucratic graveyard for innovation. You want generics? Fine. But make them interchangeable. Why should a diabetic pay $500 for an insulin pen because some regulator thinks a spring mechanism needs 18 months of human factors testing? It’s not science-it’s rent-seeking disguised as safety.

Robin Williams

January 16, 2026 AT 11:10bro i just got my epi pen refill and i was like... wait why is this $480 again? i thought generics were supposed to save us?? turns out the device is the real villain here. like imagine your life depends on a clicky thing that’s not approved to work with the chemical you’re paying for. we’re not fixing healthcare. we’re just making it weirder.

Scottie Baker

January 18, 2026 AT 11:04I’ve seen this happen to my mom. She’s got severe asthma. Got the generic albuterol inhaler? Cool. Got the generic device? Also cool. But together? Nope. Not approved. So she’s stuck paying $300 every 3 months. And the pharmacist? They just shrug. ‘Sorry, not my fault.’ But it IS your fault. You’re the one handing out half-solutions while people gasp for air. This isn’t regulation. It’s negligence with a badge.

Anny Kaettano

January 19, 2026 AT 20:57Let’s unpack this systematically: combination products are classified under PMOA (Primary Mode of Action), which dictates regulatory pathway-either drug-led or device-led. The issue isn’t just bioequivalence; it’s functional equivalence in human factors context. Human factors validation requires simulated use studies under stress conditions-panic-induced anaphylaxis, tremor during asthma attack, etc. The cost barrier isn’t arbitrary-it’s rooted in FDA’s 21 CFR Part 820 QSR and ISO 14971 risk management protocols. But yes-this is broken. We need a tiered approval framework for low-risk devices paired with generic drugs. We’re not talking about pacemakers here-we’re talking about auto-injectors that function like a stapler. Let’s stop treating them like space rockets.

Kimberly Mitchell

January 20, 2026 AT 22:18So people are upset because they can’t get a cheap version of a product that’s already overpriced? Maybe the problem isn’t the FDA-it’s that we keep letting pharmaceutical companies charge $500 for a plastic tube with a needle. If you want affordable medicine, stop enabling monopolies. Stop buying the brand. Stop complaining about the lack of generics. Stop being lazy. Go to a clinic. Get a prescription for the brand. Pay the price. Or don’t. But don’t blame the system for your privilege.

Angel Molano

January 21, 2026 AT 09:38Stop pretending this is complicated. It’s not. The FDA won’t approve it. The companies won’t invest. The patients pay. It’s a triangle of greed. Fix it. Or shut up.

Vinaypriy Wane

January 21, 2026 AT 17:59Look, I get it-this is frustrating. But let’s not forget: the device isn’t just packaging. It’s part of the therapy. If the needle depth is off by 0.5mm, the epinephrine doesn’t reach the muscle. That’s not theory. That’s clinical data. And yes, testing it costs money. But if we skip it, someone dies. And then we’ll be asking, ‘Why didn’t they do more?’ So yes, it’s slow. Yes, it’s expensive. But we’re talking about lives here. Not convenience.

Diana Campos Ortiz

January 22, 2026 AT 17:30My brother’s 12-year-old has anaphylaxis. We’ve been through this. I spent 6 months calling pharmacies, doctors, even the FDA’s hotline. Turns out, there’s ONE approved generic auto-injector combo in the entire U.S.-and it’s not stocked anywhere near us. I cried in a CVS parking lot. This isn’t policy. It’s a failure of empathy. We need better mapping of approved combos in pharmacy databases. And we need to stop acting like this is normal.

Jesse Ibarra

January 24, 2026 AT 09:30Oh wow. A whole article about how the FDA is slow? Groundbreaking. Let me guess-next you’ll tell us that the sun rises in the east? This is the same system that approved a drug that killed 500 people in 2017 because the ‘device’ was just a pill bottle. We don’t need more bureaucracy. We need to abolish the FDA’s combination product office entirely. Let the market decide. Let generics compete. Let patients choose. If they die? Then they weren’t meant to live anyway. Capitalism doesn’t care about your anxiety.

laura Drever

January 24, 2026 AT 23:41generic combo products are a mess. why does it take 2 years to test a pen? its just a needle and a liquid. the fda is a joke. also why is everyone so shocked? this is america. everything is expensive and broken.

Randall Little

January 26, 2026 AT 11:37So let me get this straight: in India, they make 10,000 generic pills a minute for pennies. But when it comes to a $20 plastic injector with a spring? Suddenly it’s a Nobel-worthy engineering feat? The U.S. spends more time proving the click sounds right than it does on actual public health. Meanwhile, other countries just say, ‘Hey, if the drug’s the same and the device looks identical, let’s go.’ We’re not protecting patients. We’re protecting profit margins under the guise of ‘safety.’

jefferson fernandes

January 27, 2026 AT 09:55This is exactly why we need a national coalition-patients, pharmacists, doctors, and manufacturers-to push for a tiered approval system for combination products. We don’t need to retest every single spring mechanism from scratch. We need a pathway for ‘device lineage’-if a generic device has already been proven equivalent to a previously approved one, and the drug is bioequivalent, then the combo should get expedited review. We’ve done this with IV bags and syringes. Why not here? We’re not asking for miracles. We’re asking for logic. And if the FDA can’t deliver that? Then we need Congress to step in. This isn’t a technical problem. It’s a moral one.