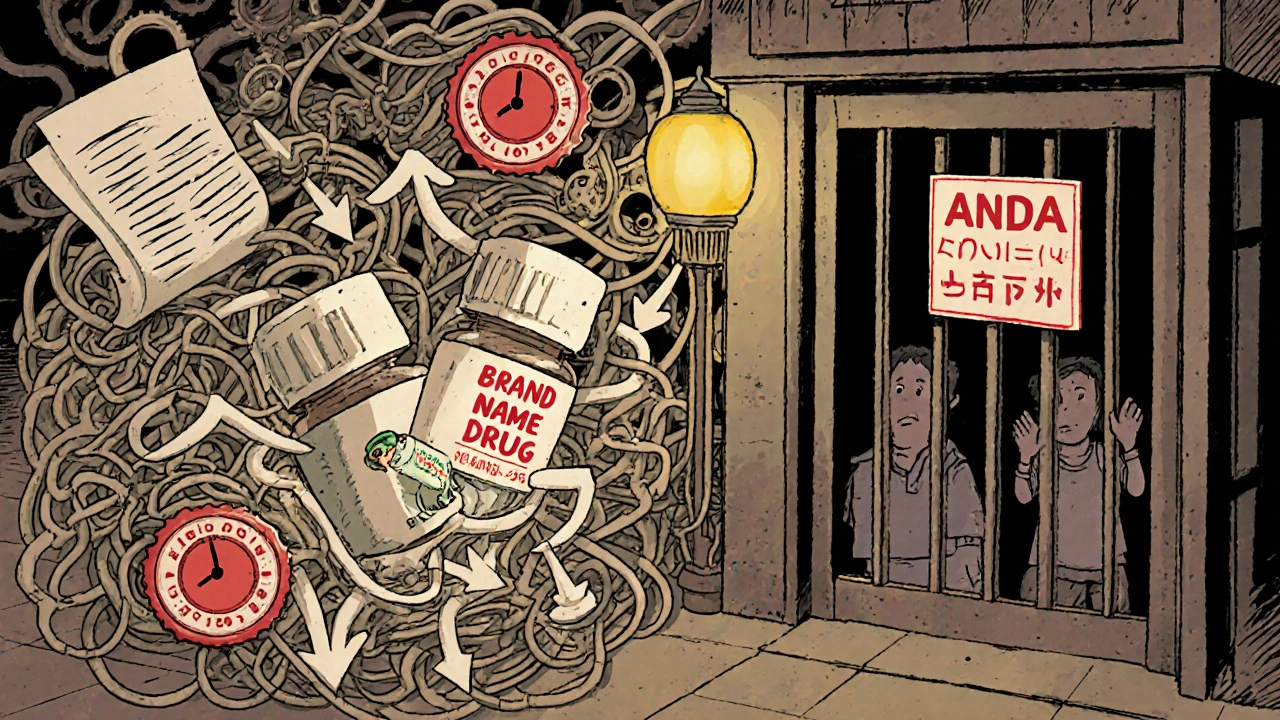

When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, you’d think generic versions would flood the market right away. But in reality, it often takes years after patent expiration before you can buy a cheaper version at your pharmacy. Why? It’s not just about the clock ticking down. There’s a whole system of legal, regulatory, and business moves that slow things down - sometimes deliberately.

Patents Aren’t the Only Barrier

Most people assume that once a drug’s 20-year patent expires, generics can jump in. But that’s not how it works. The real clock starts ticking from when the drug was first filed - not when it hit the market. Because drug development takes 8 to 10 years just to get FDA approval, most brand-name drugs only have 7 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity before patents expire. Even then, other protections kick in. The FDA gives extra exclusivity periods on top of patents. If a drug is a new chemical entity, it gets 5 years of market protection. If the maker did new clinical studies - say, to test it for a different condition - that adds 3 more years. Orphan drugs, used for rare diseases, get 7 years. And if the company tested the drug on kids, they get an extra 6 months. These layers stack up. A single drug can have multiple overlapping protections, making it hard for generics to even start the process.The ANDA Process: Simpler, But Still Slow

Generic manufacturers don’t need to redo clinical trials. They just need to prove their version works the same way as the brand-name drug - called bioequivalence. They file an Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. Sounds simple, right? But the FDA doesn’t rush these. In 2023, the average review time for an ANDA was over 25 months. That’s more than two years just waiting for approval - and that’s after the generic company has already spent 18 to 36 months developing the product. And here’s the kicker: even if the FDA approves the generic, the company can’t sell it yet. They have to wait until all patents and exclusivity periods expire. Sometimes, that’s years after approval. In fact, FDA data shows that 62% of approved generics don’t hit the market within six months of approval - not because of quality issues, but because of patent barriers.Patent Thickets and Legal Delays

Brand-name companies don’t just rely on one patent. They file dozens. The average drug has 14 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book - covering everything from the active ingredient, to how it’s made, to how it’s taken. This is called a “patent thicket.” It’s not about protecting innovation. It’s about stretching out monopoly time. When a generic company files an ANDA and says, “We don’t infringe on your patents” (a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name company can sue. That triggers a 30-month automatic stay - a legal pause on the FDA’s ability to approve the generic. But here’s the twist: studies show that the 30-month stay isn’t the main delay. The real bottleneck? The court system. On average, patent lawsuits take nearly 3.5 years to resolve. And in many cases, the brand-name company and the generic maker settle - often with the generic agreeing to delay entry in exchange for a cut of profits. These are called “reverse payment” deals, and they cost consumers $3.5 billion a year, according to the FTC.

Who Gets the First Shot?

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market rights. That’s huge. During that window, no other generic can enter. That creates a race. Companies spend millions developing multiple versions of the same drug, just in case one patent gets knocked down. But it’s risky. If they can’t get manufacturing right in time, they lose the exclusivity. About 22% of first filers forfeit the 180-day window because of production delays. This is why you sometimes see one generic come out, then nothing for months. The first company is holding the door shut - legally - while they make as much money as possible before others can join.Why Some Drugs Take Longer Than Others

Not all generics are created equal. Simple pills? They usually hit the market within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But complex drugs? That’s a whole different story. Injections, inhalers, topical creams - especially those with tricky formulations - can take 4 to 5 years. Why? Because proving bioequivalence isn’t as straightforward. The FDA needs more data. And under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), biosimilars - the generic version of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel - face even longer paths. It’s not just a pill anymore. It’s a living molecule made in a lab. The process is slower, more expensive, and more regulated. Cardiovascular drugs? On average, it takes 3.4 years after patent expiration for generics to appear. Dermatology drugs? Just 1.2 years. Why the difference? It’s not the science - it’s the money. High-revenue drugs face an average of 17 patent challenges. Lower-revenue drugs? Only 8. The more money at stake, the longer the fight.What’s Changing? What’s Not

There have been attempts to fix the system. The CREATES Act (2019) stopped brand-name companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples of their own drugs - a tactic used to delay entry. The Orange Book Transparency Act (2020) forced companies to list patents more accurately, cutting down on fake or vague claims. And in 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that secret settlements that delay generics violate antitrust law. But the core problem remains. In 2024, the FDA’s own commissioner admitted that the median time from patent expiration to generic availability is still 18 months. That’s over a year and a half where patients are paying full price for a drug that could be made for a fraction of the cost. New tools like AI are being tested to speed up bioequivalence testing - potentially cutting development time by 25%. But until the legal and financial incentives change, the system will keep favoring big pharma over patients.What This Means for You

If you’re paying for a brand-name drug, don’t assume a generic will show up when the patent expires. Check with your pharmacist. Ask if there’s a generic available - and if not, ask why. Sometimes, it’s just a matter of timing. Other times, it’s because no one has dared to challenge the patents. The savings are massive. Generics make up 92% of all prescriptions in the U.S. but only 16% of total drug spending. In 2023, they saved the system $373 billion. But if even one top drug is delayed a year, Medicare loses $1.2 billion. That’s money that could go to care, not corporate profits. The system isn’t broken - it’s working exactly as designed. The question is: who is it designed for?Why don’t generic drugs appear immediately after a patent expires?

Generic drugs don’t launch right after patent expiration because of legal delays like patent lawsuits, regulatory review times, and exclusivity periods that extend beyond the original patent. Even if the FDA approves a generic, the manufacturer can’t sell it until all patent protections and exclusivity periods are fully expired - which can take years.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generics?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drug approval in the U.S. It lets companies file Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to prove bioequivalence without redoing clinical trials. It also gave brand-name companies patent extensions to compensate for regulatory delays, and gave the first generic filer 180 days of market exclusivity. But it also created tools like the 30-month stay that can delay generic entry.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement a generic drug company files with its ANDA, claiming that a brand-name drug’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 30-month automatic delay in FDA approval if the brand-name company sues. It’s the main legal pathway for generics to challenge patents and enter the market early.

Why do some generics take longer to launch than others?

Complex drugs - like injectables, inhalers, or biologics - require more time to develop and test for bioequivalence. Drugs with many patents (called patent thickets) also face longer delays because generics must challenge each one. High-revenue drugs attract more lawsuits and settlements, which can delay entry by over a year.

Can I ask my pharmacist if a generic is coming soon?

Yes. Pharmacists have access to databases that track patent expirations and pending generic applications. If a brand-name drug is still expensive, ask if a generic is approved but not yet on the market - or if there are legal delays. Sometimes, switching to a different brand or therapeutic alternative can save money while you wait.

How do reverse payment settlements delay generic entry?

In a reverse payment settlement, the brand-name company pays the generic manufacturer to delay launching its version. Instead of competing, they split the profits. These deals are now illegal under antitrust law if they’re secret, but they still happen. The FTC estimates they delay generic entry by an average of 2.1 years and cost consumers billions annually.

Michael Fessler

November 19, 2025 AT 14:48Man, I’ve seen this play out with my dad’s diabetes med. Patent expired in 2020, but we didn’t get the generic until mid-2022. FDA approved it in late 2021, but the brand-name company sued over a formulation patent they filed in 2017 - totally unrelated to the active ingredient. ANDA process is a joke when you’ve got 17 patents layered like an onion. And don’t even get me started on the reverse payments - those are straight-up tax fraud on patients.

daniel lopez

November 21, 2025 AT 12:59THEY’RE DOING THIS ON PURPOSE. BIG PHARMA IS A CARTEL. THE FDA IS IN THEIR POCKET. YOU THINK THESE PATENT THICKETS ARE ACCIDENTAL? NO. THEY’RE DESIGNED TO KEEP YOU POOR AND SICK. THE 30-MONTH STAY? THAT’S NOT LAW - THAT’S EXTORTION. AND THE FACT THAT THEY PAY GENERIC COMPANIES TO STAY OFF THE MARKET? THAT’S BRIBERY WITH A WHITE COAT. WE’RE BEING ROBBED. AND NOBODY’S IN JAIL.

Nosipho Mbambo

November 22, 2025 AT 02:11Okay, so… the system’s broken? Cool. But why do I care? I mean, I don’t even know what an ANDA is. And I don’t have insurance. So I just buy the brand name and cry. Or, you know, skip doses. Which… is probably worse. But honestly? I’m just trying to survive. Not fight pharma.

Katie Magnus

November 22, 2025 AT 02:25Ugh. Another ‘big pharma bad’ post. Like, wow. So innovative. Did you also read that oxygen is expensive? Maybe we should all just… breathe cheaper? I mean, if you’re so mad about drug prices, why don’t you move to India? They’ve got generics for $2. Oh wait - you can’t because your body’s too American to handle it. 🙄

King Over

November 23, 2025 AT 06:14Patents expire but the drugs don’t show up. That’s wild. Makes sense though. If you’re making millions on a drug, why rush? Just wait. Courts take forever anyway. And the first generic gets a free pass for 6 months. So everyone’s just playing chess with people’s lives. Feels gross.

Johannah Lavin

November 23, 2025 AT 15:16Okay but can we just take a second to appreciate how insane this is? 💔 People are choosing between insulin and rent. And the system? It’s designed to make sure the rich stay rich and the sick stay sick. I had a friend who died because she couldn’t afford her asthma inhaler. The generic came out 14 months after patent expiry. FOURTEEN MONTHS. That’s a whole season of grief. We need to burn this whole thing down. 🔥

Ravinder Singh

November 24, 2025 AT 17:47Bro, I’ve seen this in India too - even though generics are cheaper here, big pharma still uses patent tricks to delay entry. But here’s the silver lining: community pharmacists are becoming the real heroes. They track patent expirations, call manufacturers, and sometimes even import from trusted international sources. It’s messy, but it works. And if you’re reading this - ask your pharmacist. They know more than your doctor sometimes. 🙏

Russ Bergeman

November 25, 2025 AT 18:57Wait - so the FDA takes 25 months to approve a generic? That’s not a delay - that’s incompetence. And you’re telling me they’re not cutting corners? Then why is the approval rate so low? This isn’t about patents - it’s about bureaucratic laziness. Fix the FDA. Stop blaming pharma. The real villain is the government that can’t manage a simple approval queue.

Dana Oralkhan

November 26, 2025 AT 12:11Thank you for writing this. I’ve been a nurse for 18 years, and I’ve watched patients cry because they can’t afford their meds. I’ve had to call pharmacies every week asking, ‘Is the generic in yet?’ And sometimes the answer is no - even though it’s been approved for 10 months. The system doesn’t care about people. It cares about spreadsheets. But we do. And we’re not giving up.

Jeremy Samuel

November 28, 2025 AT 01:19patent expiratoin? more like patent expiratoin. jk. but seriously, why do these companies get to keep playing games? i mean, i get that they want to make money, but come on. if you spent 10 years developing a drug, you got your shot. now let the market breathe. i’m not paying $500 for a pill that costs $3 to make. its not rocket science.

Destiny Annamaria

November 28, 2025 AT 20:07Y’all don’t get it - this isn’t just about drugs. It’s about trust. We used to believe in science. Now we just see profit. I grew up thinking doctors and pharma were saving lives. Now I know they’re just managing money. And that hurts more than any pill ever could. 🌍💔

Ron and Gill Day

November 29, 2025 AT 19:31Wow. Another ‘pharma is evil’ article. You know what’s evil? People who don’t take responsibility for their health. If you’re on insulin, maybe stop eating donuts. If you’re on statins, maybe start walking. Stop blaming corporations for your bad lifestyle choices. The system works fine - you just don’t like the price tag.

Alyssa Torres

November 30, 2025 AT 06:31Okay, but what if we reimagined this entirely? What if we treated medicine like public infrastructure - like roads or water? No patents. No exclusivity. Just open-source drug development funded by public grants. Imagine if every drug discovery was a public good. No more 180-day monopolies. No more reverse payments. Just science, for people. It’s not crazy - it’s how vaccines were developed during COVID. Why can’t we do it for everything?

Aruna Urban Planner

December 2, 2025 AT 04:09This is the quiet tragedy of modern capitalism - innovation is weaponized. The patent system was meant to incentivize discovery, not to extend monopolies. But when you turn life-saving medicine into a financial instrument, you don’t just delay access - you redefine human dignity as a commodity. The real question isn’t how long it takes for generics to appear - it’s whether we still believe health is a right, or just another market segment.