Azithromycin Liver Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment

This tool evaluates your risk of azithromycin-induced liver injury based on factors discussed in the article.

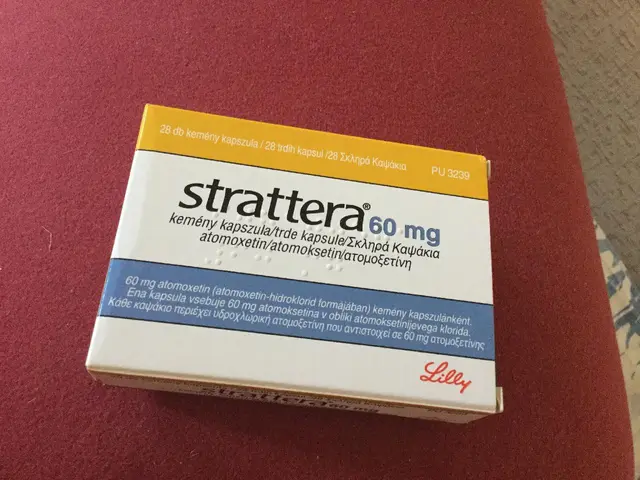

Azithromycin is one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in the world. You’ve probably heard of it by its brand name, Zithromax. It’s used for sinus infections, bronchitis, pneumonia, strep throat, and even sexually transmitted infections like chlamydia. Doctors love it because it’s easy to take - often just one pill a day for three to five days. But behind its convenience lies a quiet, underreported danger: liver damage.

For years, azithromycin was considered one of the safest antibiotics when it came to the liver. Many patients were told, "It won’t hurt your liver." That belief is outdated. New data from the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, and major medical journals show azithromycin is now among the top 10 causes of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) in the U.S. And unlike some other antibiotics, the damage doesn’t always show up while you’re still taking it. Often, it shows up days - even weeks - after you’ve finished the course.

How Azithromycin Damages the Liver

Azithromycin doesn’t attack the liver in the same way as, say, acetaminophen overdose. It doesn’t cause massive, immediate cell death. Instead, it triggers a delayed, unpredictable reaction - what doctors call an "idiosyncratic" injury. This means it doesn’t happen to everyone, but when it does, it can be serious.

Most cases involve cholestatic liver injury. That means the flow of bile from the liver slows or stops. You might not feel anything at first. But then, symptoms creep in: yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice), dark urine, itchy skin, extreme fatigue, and pain under the right ribs. Blood tests will show elevated liver enzymes - especially alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bilirubin. In some cases, ALT (another liver enzyme) spikes too, signaling direct damage to liver cells.

What’s unusual about azithromycin is timing. A 2015 study in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology found that 89% of patients developed symptoms after they stopped taking the drug. The average time from finishing the pills to noticing jaundice? Nine days. That’s why many doctors miss it. They think, "The medicine’s gone. It can’t be the cause." But it can - and often is.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone who takes azithromycin gets liver damage. The overall risk is low - about 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 65,000 prescriptions. But certain people are far more vulnerable.

- People with existing liver disease - Even mild fatty liver or cirrhosis increases risk. The European Medicines Agency advises avoiding azithromycin in patients with severe liver impairment.

- Older adults (65+) - Nearly 40% of severe cases occur in this group, according to FDA adverse event data.

- Those on long-term therapy - While most courses are 3-5 days, some patients (like those with chronic lung disease or cystic fibrosis) take it for weeks or months. In these cases, liver enzyme elevations jump to 5-7%.

- People taking other liver-affecting drugs - Combining azithromycin with medications like atovaquone (used for babesiosis) has led to severe liver failure in documented cases.

Interestingly, there’s no clear link to genetics, alcohol use, or obesity. It’s not about how you live - it’s about how your body reacts to the drug.

How It Compares to Other Antibiotics

Not all antibiotics are equal when it comes to liver safety. Here’s how azithromycin stacks up:

| Antibiotic | Typical Liver Injury Pattern | Incidence of DILI | Recovery Time | Transplant Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | Cholestatic or mixed | 1 in 2,500-65,000 | 4-8 weeks (92% recover) | 0.7% of DILI cases |

| Erythromycin | Cholestatic | 1 in 1,000 | 6-12 weeks | 1.2% |

| Clarithromycin | Cholestatic | 1 in 10,000 | 4-6 weeks | 0.3% |

| Doxycycline | Minimal risk | Very rare | N/A | N/A |

| Isoniazid (TB drug) | Hepatocellular | 1 in 10-20 | 3-6 months | 5% |

| Tedizolid | No significant risk | Negligible | N/A | N/A |

Even though azithromycin has a lower incidence than erythromycin, it’s far more widely used. That’s why it causes more total cases of liver injury. In the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN), azithromycin ranked third among all antibiotics linked to liver damage - behind amoxicillin-clavulanate and isoniazid.

What Happens When It Goes Wrong

Most people recover fully if caught early. But some don’t.

A 2023 case report in Annals of Internal Medicine described a 62-year-old man who took azithromycin for pneumonia. He finished the 5-day course. Two weeks later, his skin turned yellow. His bilirubin hit 28.7 mg/dL - over 15 times the normal level. His liver was failing. He needed a transplant.

That’s rare. But it’s real. About 0.7% of azithromycin-related liver injuries lead to chronic liver damage or transplant. And in 63% of biopsy-proven cases, there’s evidence of "vanishing bile duct syndrome" - where the tiny tubes that carry bile out of the liver disappear permanently.

Even if you don’t need a transplant, recovery can take months. One patient in a 2024 case study had elevated liver enzymes for over 18 months after a single course. She needed multiple ERCP procedures to clear blocked bile ducts.

What Doctors Should Do - And Often Don’t

Here’s the scary part: most doctors still don’t think of azithromycin as a liver risk.

A Medscape poll of 1,247 primary care doctors in 2023 found that 78% rarely consider liver damage when prescribing azithromycin - even though 92% knew it was possible. That’s a huge gap between knowledge and action.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) has clear guidelines: if a patient on azithromycin has ALT more than 3 times the upper limit of normal, or bilirubin more than 2 times normal, stop the drug immediately. That’s called Hy’s Law - and it predicts a 10-14% chance of acute liver failure.

But here’s the problem: patients often don’t get liver tests at all. No one checks ALT or bilirubin before or after a simple course of Zithromax. And when jaundice appears, it’s frequently mistaken for viral hepatitis. One woman in a LiverTox case report was misdiagnosed for three weeks - delaying treatment and worsening her injury.

What You Should Do

If you’re prescribed azithromycin, here’s what you need to know:

- Know the warning signs. Jaundice, dark urine, itching, extreme tiredness, or pain under your right ribs - especially after finishing the pills - could mean liver trouble.

- Don’t assume it’s safe. Just because it’s common doesn’t mean it’s harmless. Ask your doctor: "Is there a safer alternative?" For respiratory infections, doxycycline is just as effective and has almost no liver risk.

- Get tested if you’re high-risk. If you’re over 65, have fatty liver, or take other medications, ask for a baseline liver test before starting. A simple blood test can catch early damage.

- Don’t ignore symptoms after finishing. The damage often starts after the last pill. If you feel off two weeks later, mention azithromycin to your doctor - even if you think it’s unrelated.

For most people, azithromycin is fine. But for some, it’s a silent threat. The key is awareness - not fear.

What’s Changing Now?

The FDA updated the drug label in 2018 to include stronger warnings about liver injury. The European Medicines Agency now advises against using azithromycin in severe liver disease. Hospitals like Kaiser Permanente now require liver tests for patients on courses longer than 7 days.

Research is moving fast. A 2024 mouse study suggests azithromycin may block a natural liver-protecting pathway called Nrf2. If this holds true in humans, it could lead to new protective drugs - like sulforaphane (found in broccoli sprouts) - being tested in 2025.

But for now, the message is simple: azithromycin is not as liver-safe as we thought. It’s still a powerful, useful tool - but it’s not risk-free. The days of calling it "safe for the liver" are over.

Sumler Luu

December 25, 2025 AT 22:56I took azithromycin last year for a bad sinus infection and felt fine-until two weeks later when my skin turned yellow. My doctor brushed it off as "viral hepatitis" until I pushed for liver tests. Turns out, my ALP was through the roof. No one warned me. I’m lucky I caught it before it got worse. If you’re on this drug, don’t wait for symptoms to get bad. Get tested.

Also, why is this still not standard practice? A simple ALT panel before prescribing could save lives.

sakshi nagpal

December 26, 2025 AT 02:26As someone from India where antibiotics are often prescribed without proper diagnostics, this article is a wake-up call. In my community, azithromycin is the go-to for everything from coughs to fevers-even in children. We assume it’s safe because it’s cheap and widely available. But this data changes everything.

Doctors need to be educated, and patients need to be empowered to ask: "What are the risks?" Not just "How many pills do I take?"

Nikki Brown

December 27, 2025 AT 15:54Wow. Just... wow. 😤 So people are still taking this like it’s candy? I’m not surprised. The medical industry is a profit machine, and convenience always wins over safety. You want to be lazy? Fine. But don’t blame the liver when it gives up. This isn’t "rare"-it’s predictable. And if your doctor didn’t warn you? Fire them.

Also, why are we still using this? Doxycycline is cheaper, safer, and works just as well for 80% of cases. Stop being sheep.

PS: I’m not mad. I’m just disappointed. 😔

Peter sullen

December 28, 2025 AT 02:35It is imperative to underscore the clinical significance of azithromycin-induced hepatotoxicity, particularly within the context of idiosyncratic, delayed-onset drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The pharmacokinetic profile of azithromycin-characterized by extensive tissue penetration and prolonged half-life-exacerbates the risk of cumulative hepatocellular stress, especially in patients with preexisting hepatic insufficiency.

Per Hy’s Law criteria, an ALT >3x ULN coupled with total bilirubin >2x ULN constitutes a red flag requiring immediate cessation and hepatology referral. The 0.7% transplant rate, while statistically low, is clinically unacceptable given the drug’s ubiquity. We must institutionalize pre-prescription liver enzyme screening in high-risk cohorts, particularly geriatric populations and polypharmacy patients.

Furthermore, the Nrf2 pathway inhibition hypothesis, per the 2024 murine model, presents a compelling mechanistic rationale for future prophylactic interventions, such as sulforaphane co-administration. This warrants phase II clinical trials without delay.

Natasha Sandra

December 29, 2025 AT 16:22OMG I just realized I took this last month and felt kinda tired but thought it was just stress 😳

Now I’m checking my email for my last blood work… if I’m yellow, I’m suing my doctor. 😤

Also, why does every antibiotic come with a warning label except this one?? Like, I can’t even buy a soda without a warning, but this? Nah. Just pop it. 😒

PS: Broccoli sprouts are now on my grocery list. 🥦💪

Erwin Asilom

December 30, 2025 AT 14:57I’ve been a nurse for 18 years. I’ve seen patients recover from azithromycin liver injury. I’ve also seen them die because no one connected the dots. This isn’t just about the drug-it’s about culture. We treat antibiotics like vitamins. We don’t monitor. We don’t follow up. We assume.

Every time someone says "it’s safe," they’re not just wrong-they’re dangerous. If you’re prescribing this to someone over 65 or with fatty liver, you’re gambling with their life. And if you’re taking it? Pay attention. Your liver doesn’t scream. It whispers. Until it doesn’t.

Sandeep Jain

January 1, 2026 AT 13:57bro i took this for my cough last winter and felt fine but my mom kept asking if my eyes were yellow and i was like "mom chill" but then she made me go to clinic and turns out my bilirubin was high 😳

doc said "you got lucky" and now i tell everyone about this. if you feel weird after antibiotics, dont ignore it. its not just "tiredness". its your liver screaming. 🫠

roger dalomba

January 2, 2026 AT 09:18So let me get this straight: we’ve got a $12 antibiotic that’s now #3 on the liver injury list… and we still give it out like free candy at a parade? Genius. 💪

Next up: prescribing cyanide for strep throat. At least it’s convenient.