Proton pump inhibitors, or PPIs, are one of the most common medications prescribed for heartburn, acid reflux, and ulcers. Brands like Prilosec, Nexium, and Protonix sound harmless - many people take them daily for years without thinking twice. But here’s the problem: proton pump inhibitors aren’t meant to be taken forever. And if you’ve been on them for more than a few months, you might be at risk for side effects you didn’t even know about.

How PPIs Work - And Why They’re So Popular

PPIs block the final step of stomach acid production. They target the proton pumps in the stomach lining - the tiny engines that churn out acid to digest food. By shutting them down, PPIs reduce acid by up to 90%. That’s why they’re so effective for healing erosive esophagitis, treating ulcers, and managing chronic GERD. Most people feel better within days.

But here’s the catch: they take 1 to 4 days to kick in fully. That’s why they’re not good for quick relief. If you need instant comfort, antacids like Tums or H2 blockers like Pepcid work faster. PPIs are designed for longer-term control, not emergency fixes.

Over 15 million Americans take prescription PPIs daily. Another 7 million buy them over-the-counter - and many keep using them long past the 14-day limit the FDA says is safe. Why? Because they work. And because people assume they’re harmless. That’s the dangerous myth.

The Real Long-Term Risks

There’s solid evidence linking long-term PPI use to several health problems. Not all of them are common, but they’re serious enough to warrant caution.

- Low magnesium levels (hypomagnesemia): This is rare, affecting about 0.5% to 1% of long-term users, but it can be life-threatening. Symptoms include muscle cramps, irregular heartbeat, and seizures. The FDA requires doctors to check magnesium levels in people taking PPIs for more than a year.

- Increased fracture risk: Studies show people on PPIs for 4 to 8 years have up to a 55% higher risk of hip fractures. The reason? Less stomach acid means less calcium absorption. The good news? This risk drops back to normal after stopping PPIs for over two years.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency: About 10% to 15% of long-term users develop low B12. That’s because acid is needed to pull B12 out of food. Without it, you can get tired, numb in your hands and feet, or even develop nerve damage. Blood tests can catch this early.

- C. diff infections: PPIs raise your risk of this dangerous gut infection by nearly 2 times. It causes severe diarrhea and can land you in the hospital. This risk is highest in older adults or those in hospitals or nursing homes.

- Acute interstitial nephritis: A rare but serious kidney inflammation that can lead to chronic kidney disease. The FDA flagged this in 2016. It’s not common, but it’s irreversible if not caught early.

- Rebound acid hypersecretion: This isn’t a disease - it’s a withdrawal effect. After months or years of suppressing acid, your stomach overcompensates. When you stop suddenly, you get worse heartburn than before. Up to 80% of long-term users experience this. It’s why quitting cold turkey often fails.

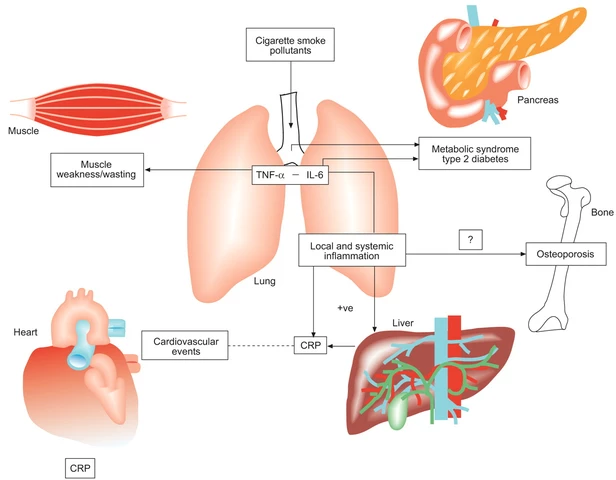

Some studies have linked PPIs to dementia, heart disease, and stomach cancer. But higher-quality research hasn’t confirmed these links. Experts believe these associations may come from other factors - like age, obesity, or smoking - not the PPI itself. Still, the FDA and major medical groups agree: if you don’t need it, don’t take it.

When You Should Stop

Not everyone needs PPIs long-term. In fact, most people don’t. Here’s when you should consider stopping:

- You’re taking it for mild heartburn or occasional indigestion without a confirmed diagnosis.

- You’ve been on it for more than 8 weeks for uncomplicated GERD.

- You’re using over-the-counter PPIs longer than 14 days, more than once every 3 months.

- You have no history of ulcers, esophagitis, or Barrett’s esophagus.

- You’re on multiple medications - PPIs can interfere with absorption of blood thinners, antifungals, and some antibiotics.

Doctors often prescribe PPIs out of habit, not necessity. A 2023 study found that 40% of primary care prescriptions for PPIs were for dyspepsia - a vague term for upset stomach - without endoscopy or testing. That’s not evidence-based care.

If you’ve been on PPIs for over a year, ask yourself: Do I still have symptoms? Or am I just afraid to stop?

How to Stop Safely - No Rebound Heartburn

Stopping PPIs cold turkey is a recipe for misery. Rebound acid can last weeks. But there’s a better way.

The American College of Gastroenterology recommends a slow taper:

- Reduce your dose by half (e.g., from 40mg to 20mg) for 1-2 weeks.

- Switch to taking it every other day for another 1-2 weeks.

- Then go to on-demand use: take it only when symptoms flare up.

- After 2-4 weeks of on-demand use, try stopping completely.

During this time, you can use antacids (Tums, Rolaids) or H2 blockers (famotidine) for breakthrough symptoms. They’re safe for occasional use and won’t cause rebound.

Also, make lifestyle changes. Avoid large meals, late-night eating, caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods. Elevate the head of your bed. Lose weight if you’re overweight. These steps alone can cut symptoms by 60-70% in many people.

What to Do If You’re Still Symptomatic After Stopping

If your heartburn comes back after stopping, don’t panic. That doesn’t mean you have to go back on PPIs forever. Talk to your doctor. You might need:

- An endoscopy to check for actual damage in your esophagus.

- Testing for H. pylori - a bacteria that causes ulcers and can mimic GERD.

- Trying a different class of medication, like a P-CAB (potassium-competitive acid blocker). Vonoprazan is one example - it’s newer and may have fewer long-term risks, though it’s not yet widely available in the U.S.

Some people have a condition called functional heartburn - where the esophagus is overly sensitive, even though acid levels are normal. These patients don’t benefit from acid suppression at all. They need different treatments, like nerve-modulating drugs or cognitive behavioral therapy.

Over-the-Counter PPIs: A Hidden Problem

Buying PPIs without a prescription sounds convenient. But it’s also dangerous. The FDA clearly says: don’t use OTC PPIs for more than 14 days, and only once every 3 months. Yet 25% of users ignore that warning.

Why? Because they feel better. And because the packaging doesn’t scream “RISK.” It says “relieves heartburn” - not “may cause kidney damage.”

If you’ve been buying Prilosec OTC for months, you’re not alone. But you’re also not safe. Talk to your doctor before continuing. There are safer, short-term options for occasional heartburn.

The Bottom Line

PPIs are powerful tools - but they’re not candy. They work brilliantly for the right people at the right time. But for millions, they’ve become a daily habit with hidden costs.

If you’re on a PPI and don’t know why, ask your doctor. If you’ve been on it for over a year, consider a taper plan. If you’re using OTC versions beyond 14 days, it’s time to rethink your approach.

Stopping PPIs isn’t about fear - it’s about balance. Your stomach needs acid to digest food, absorb nutrients, and protect you from infection. Suppressing it long-term isn’t harmless. It’s a trade-off. And you deserve to know what you’re trading.

Can I stop taking PPIs cold turkey?

No, stopping abruptly often causes severe rebound heartburn because your stomach overproduces acid after long-term suppression. Up to 80% of long-term users experience this. Instead, taper the dose slowly over weeks, switch to on-demand use, and use antacids or H2 blockers for symptom relief during the process.

How long is too long to be on PPIs?

For most conditions like GERD or ulcers, 4 to 8 weeks is enough. If you still need it after that, your doctor should reassess. Long-term use - defined as more than a year - increases risks like low magnesium, B12 deficiency, and bone fractures. Regular check-ups and attempts to stop (called "drug holidays") every 6 to 12 months are recommended.

Do PPIs cause kidney damage?

PPIs can cause acute interstitial nephritis - a rare but serious kidney inflammation - especially in the first few months of use. While some studies link long-term use to chronic kidney disease, the evidence isn’t clear-cut. The FDA warns about this risk, so if you’re on PPIs long-term, get your kidney function checked periodically.

Are there safer alternatives to PPIs?

For occasional heartburn, antacids (Tums, Rolaids) and H2 blockers (famotidine, ranitidine) are safer short-term options. For chronic GERD, lifestyle changes - like losing weight, avoiding late meals, and elevating your bed - can be just as effective as medication for many people. In some cases, newer drugs like vonoprazan (a P-CAB) may offer similar relief with fewer long-term risks, but they’re not yet widely available.

Can PPIs cause vitamin deficiencies?

Yes. Long-term PPI use can lead to low levels of vitamin B12, magnesium, calcium, and iron. Stomach acid helps break down food so your body can absorb these nutrients. Without enough acid, absorption drops. If you’ve been on PPIs for over 2 years, ask your doctor to check your blood levels for these nutrients.

Is it true PPIs increase the risk of dementia?

Some early studies suggested a link, but higher-quality research has not confirmed it. Experts believe these associations may be due to other factors - like age, poor diet, or other medications - rather than PPIs themselves. The FDA and major medical groups do not list dementia as a confirmed risk.

Why do doctors keep prescribing PPIs if they have risks?

Because they work - really well. For people with severe esophagitis or ulcers, PPIs are life-changing. The problem is overprescribing. Many patients get PPIs for mild symptoms without testing, or continue them out of habit. Doctors are now being trained to question long-term use and encourage deprescribing when appropriate.

How do I know if I really need a PPI?

If you have confirmed damage like erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, or a peptic ulcer, then yes - you likely need it. But if you only have occasional heartburn, bloating, or indigestion without endoscopic proof of disease, you probably don’t. Ask your doctor: "What exactly am I treating?" and "Is there a test to confirm I need this?"

Bret Freeman

December 23, 2025 AT 20:22People don't realize how addicted they are to these pills. I was on Nexium for 7 years because I thought it was just "normal" to have heartburn. When I finally tapered off, I was in agony for three weeks. My doctor never warned me about rebound. Now I eat like a rabbit, sleep upright, and still have the occasional flare-up-but at least my kidneys aren't screaming.

EMMANUEL EMEKAOGBOR

December 23, 2025 AT 20:39Thank you for this comprehensive overview. In Nigeria, where access to specialist care is limited, many patients self-medicate with OTC PPIs for months without medical supervision. The cultural norm is to treat symptoms, not investigate causes. This article should be translated and distributed in primary care clinics across West Africa.

Gray Dedoiko

December 25, 2025 AT 13:52I stopped my PPI last year after reading this same info from my GI doc. Tapered over 6 weeks, used Tums when needed, and honestly? My digestion improved. I used to think acid = bad. Turns out, too little acid is worse. My bloating vanished, my energy came back. Still eat spicy food sometimes. No regrets.

Paula Villete

December 25, 2025 AT 19:16So let me get this straight-we’re supposed to believe that Big Pharma didn’t market these like candy because they knew people would take them forever? And yet we’re shocked when people get kidney damage? The FDA’s warning label is smaller than the font on the bottle that says "relieves heartburn in 1 minute."

Georgia Brach

December 26, 2025 AT 22:25The data on dementia and heart disease is correlational, yes-but so is the data linking smoking to lung cancer in the 1950s. We ignored that too. PPIs suppress acid, which alters gut microbiota, which alters systemic inflammation, which alters neurological and cardiovascular pathways. The mechanism is plausible. The studies are growing. Don’t be the person who says "I’m fine" until it’s too late.

Katie Taylor

December 27, 2025 AT 17:22If you're still on PPIs after a year, you're not managing your health-you're outsourcing it. Your doctor gave you a Band-Aid and called it a cure. Time to grow up. Eat better. Lose weight. Stop lying down after dinner. These aren't "lifestyle changes"-they're basic human behavior. You wouldn't smoke and blame the lung machine for your cancer. Stop blaming your stomach acid.

Lu Jelonek

December 29, 2025 AT 02:50As someone who grew up in Japan, where herbal remedies and dietary adjustments are the first line of defense for digestive issues, I find it alarming how quickly Americans turn to pharmaceuticals. In Osaka, they use shiso leaf, ginger tea, and mindful eating to manage reflux. No pills needed. Maybe we’ve forgotten how to listen to our bodies.

siddharth tiwari

December 29, 2025 AT 11:18They’re not just hiding the risks-they’re hiding the truth. PPIs are part of a bigger plan to make us dependent. The FDA? Controlled. Doctors? Paid. The real cause of heartburn? Glyphosate in our food. Your stomach isn’t making too much acid-it’s trying to digest poison. Stop taking the pills. Start eating organic. Or keep dying quietly.

Adarsh Dubey

December 30, 2025 AT 19:09I’ve been off PPIs for 18 months now. Started with a 50% taper, used famotidine sparingly, and focused on sleep posture and meal timing. No rebound. No drama. My B12 was low, so I started injections-simple fix. This isn’t rocket science. It’s basic physiology. Why do we make it so complicated?

Bartholomew Henry Allen

December 31, 2025 AT 21:15Stop taking PPIs. Stop being weak. Eat less. Move more. Stop complaining. This country is soft. You want relief? Build discipline. Your body is not broken. Your habits are. Fix them or live with the consequences.

Andrea Di Candia

January 1, 2026 AT 14:20I used to think PPIs were the answer until I started feeling numb in my fingers. Turns out my B12 was at 180. After switching to sublingual B12 and cutting back on the pill, my symptoms disappeared. It’s not about fear-it’s about awareness. We’ve been taught to fix symptoms, not understand systems. This post? It’s a gift.

bharath vinay

January 2, 2026 AT 17:06They’re lying. PPIs cause cancer. They’re in the water. The WHO knows. Your microbiome is dead because of this. They don’t want you to heal. They want you to pay monthly. Watch the documentary "PPI: The Silent Poison"-it’s on a hidden server. Google it. You’ll find it.

Dan Gaytan

January 3, 2026 AT 01:40Just wanted to say thank you for posting this. I was on Prilosec for 5 years and had no idea I was at risk for kidney issues. I tapered off last month with the help of my doctor and now I feel like I’ve been sleeping my whole life. 🙏