When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But what if the batch of generic drug you’re holding is subtly different from the one tested in the lab? This isn’t just a theoretical concern-it’s a real, documented problem that regulators are only now starting to fix.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

Bioequivalence is the gold standard for approving generic drugs. It means the generic version delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed as the brand-name drug. The test? Measure two key numbers: AUC (how much drug gets absorbed over time) and Cmax (how high the peak concentration goes). If the ratio of these values between the generic and brand drug falls between 80% and 125%, regulators say they’re equivalent.This 80-125% rule has been the global standard since the 1990s. It works well… if you’re comparing two identical batches. But here’s the catch: no two batches of a drug are ever exactly the same.

Batch Variability Isn’t Noise-It’s the Signal

Manufacturing drugs isn’t like pouring water into bottles. Small changes in temperature, mixing time, or raw material source can shift how the drug dissolves or gets absorbed. Studies show that batch-to-batch variability can account for 40% to 70% of the total error seen in bioequivalence studies. That’s not a tiny glitch-it’s the biggest source of uncertainty in the whole process.Imagine testing a generic drug against one single batch of the brand-name version. If that brand batch happens to be unusually consistent, the generic might look perfect-even if it’s not. Or worse: if the brand batch is unusually variable, the generic might fail even though it’s perfectly fine. This isn’t speculation. A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics proved that conventional bioequivalence tests often get it wrong because they ignore this variability.

Why the 80-125% Rule Falls Short

The current system treats every drug the same. Whether it’s a simple tablet or a complex inhaler, the same 80-125% window applies. But that doesn’t make sense.Take nasal sprays or inhalers. These products depend on precise particle size and spray pattern. Minor manufacturing changes can dramatically alter how much drug reaches your lungs. Yet, under current rules, a manufacturer might test just one batch of the brand and one batch of the generic. If those two batches happen to match, approval is granted-even if other batches of the generic could behave very differently.

This is called “confounded bioequivalence.” The result isn’t just statistical noise-it’s a real risk to patient safety. Some patients might get a batch that works fine. Others might get one that doesn’t deliver enough drug. And because regulators don’t test multiple batches, they never know.

The New Approach: Testing More Batches

The solution isn’t to throw out bioequivalence-it’s to do it right.Leading experts and regulators now agree: you need to test multiple batches. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and FDA are moving toward requiring at least three batches of the reference drug and two of the generic. This isn’t just a suggestion-it’s becoming mandatory for complex products like inhalers, injectables, and topical creams.

Instead of just comparing one generic batch to one brand batch, you compare the average of multiple test batches to the average of multiple reference batches. This gives you a much clearer picture of whether the generic is truly equivalent across its entire production line.

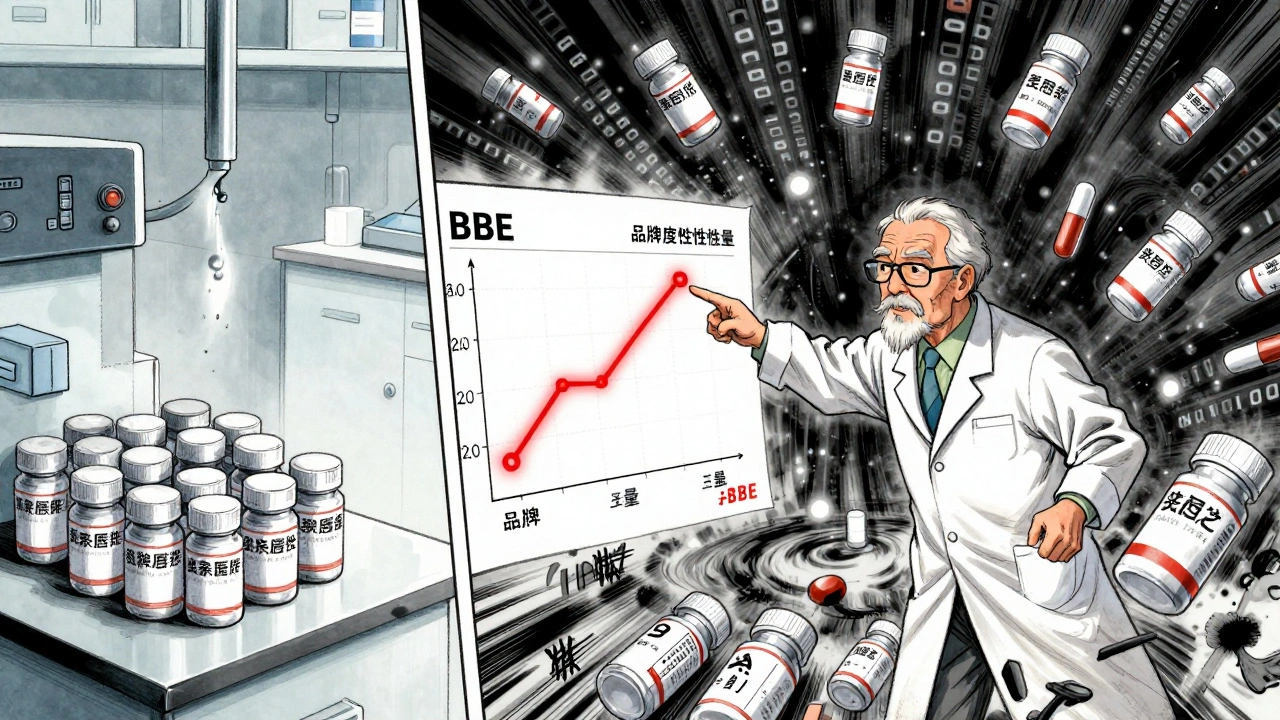

Betweeen-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE): A Game-Changer

One of the most promising new methods is called Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE). Instead of forcing everything into the 80-125% box, BBE asks: How variable is the brand drug itself?If the brand drug’s batches vary by 15% from each other, then the generic should be allowed to vary by a similar amount. BBE compares the difference between the generic and brand averages to the brand’s own batch variability. If the difference is less than twice the brand’s between-batch standard deviation, the generic passes.

This approach is smarter. It doesn’t treat all drugs as if they’re simple tablets. It lets the data speak. A 2020 study in Pharmaceutical Statistics showed that BBE correctly identifies true bioequivalence more often than the old method-especially when batch variability is high.

What’s Changing Right Now

Regulators are catching up. In June 2023, the FDA released a draft guidance titled Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies. It’s not final yet, but it’s a clear signal: the old way is outdated.The EMA held a workshop in 2023 and called batch variability one of the top three challenges in generic drug approval. Industry surveys show that 78% of major generic manufacturers now test multiple batches-up from just 32% in 2018. That’s not because they’re being nice. It’s because they know the old system is risky and unreliable.

Even the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is working on new guidelines (Q13) for continuous manufacturing, which will require better statistical tools to prove consistency across production runs. This isn’t about slowing down generics-it’s about making sure they’re safe.

What This Means for You

As a patient, you don’t need to check batch numbers. But you should know that the system is improving. The days of approving generics based on a single test batch are ending. The new standard is multi-batch testing, better statistics, and smarter rules.That means fewer false negatives-where good generics get rejected-and fewer false positives-where bad ones slip through. It also means generic drug approvals might take a little longer. But the trade-off? More reliable medications. Less guesswork. Better outcomes.

For people taking critical drugs-like blood thinners, epilepsy meds, or thyroid hormones-this shift matters. A small difference in absorption can mean the difference between control and crisis. The old system didn’t protect against that. The new one does.

The Bottom Line

Bioequivalence isn’t broken. It just needed an upgrade. The 80-125% rule was a good start, but it was built for a simpler time. Today’s drugs are more complex. Manufacturing is more advanced. And we now know that batch variability isn’t just noise-it’s the core of the problem.The future of generic drugs isn’t about cheaper pills. It’s about smarter science. Testing more batches. Using better stats. Accepting that variability exists-and building rules that account for it.

If you’ve ever wondered why some generics work better than others, this is why. And the system is finally fixing it.

Louis Llaine

December 8, 2025 AT 05:50So let me get this straight-we’re spending millions to test three batches of a pill so we can be *sure* it won’t kill someone… but we still let pharmacies swap out generics like trading cards? 🤡

Helen Maples

December 8, 2025 AT 06:01The current bioequivalence framework is statistically indefensible. Relying on single-batch comparisons ignores the fundamental variability inherent in pharmaceutical manufacturing. The proposed shift to multi-batch testing and Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE) is not merely an improvement-it is a necessary evolution grounded in sound pharmacokinetic principles and risk-based regulation.

David Brooks

December 9, 2025 AT 17:35THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING I’VE READ ALL YEAR. 🙌

Imagine if your heart medication varied like your coffee order-some days you get a double espresso, other days a lukewarm drip. That’s what patients are dealing with. Thank you for exposing this. The system is waking up-and thank god.

Jennifer Anderson

December 10, 2025 AT 05:58so like… if the brand drug itself is all over the place, why are we holding the generic to a perfect standard? that’s just dumb.

we should be like ‘hey brand, how janky is your stuff?’ and then let the generic be kinda like that. makes sense lol

Sadie Nastor

December 11, 2025 AT 20:29Thank you for writing this. I’ve been on the same generic for years and sometimes I swear it just… doesn’t work the same. I thought it was me. 😅

Knowing this isn’t just ‘my bad’ but a real system flaw? That’s so validating. Hope this change happens fast.

Nicholas Heer

December 12, 2025 AT 20:30Big Pharma and the FDA are in bed together. This ‘multi-batch’ thing? A distraction. They’re just trying to make generics cost more so you keep buying the brand-name $200 pills. The real goal? Control. Surveillance. You think they care if your seizure meds work? Nah. They care if you keep paying.

Kurt Russell

December 14, 2025 AT 03:59STOP SCROLLING. THIS IS HUGE.

Think about it: if you’re taking a blood thinner and your generic batch is 15% weaker, you could clot. 15% stronger? You could bleed out.

This isn’t about money-it’s about lives. And now? We’re finally fixing it. Let’s cheer this win. 🚀

Stacy here

December 15, 2025 AT 10:52There’s a reason why people feel ‘different’ on generics. It’s not placebo. It’s not ‘psychological.’ It’s the fact that the entire regulatory framework is built on a lie: that drugs are static.

But biology isn’t static. Manufacturing isn’t static. And yet we treat them like they are. This isn’t science-it’s ritual. And the ritual is crumbling.

Kyle Flores

December 16, 2025 AT 04:51Just want to say I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen patients crash because a generic didn’t work right. No one ever connected the dots until now.

Thanks for making this so clear. This change? Long overdue. Let’s push for it to be mandatory for everything-not just inhalers.

Ryan Sullivan

December 17, 2025 AT 01:43Let’s be honest: the 80–125% rule was always a political compromise, not a scientific one. It was designed to accelerate generic entry, not ensure therapeutic equivalence. What’s astonishing is how long it took for the field to admit this. The EMA and FDA are finally applying Bayesian logic to pharmacokinetics. Finally. The rest of the world should follow.

Olivia Hand

December 17, 2025 AT 17:33Has anyone looked at how this affects pediatric dosing? Kids are more sensitive to absorption differences. If a brand’s batch variability is ±12%, but the generic is ±18%, that could mean a 20% difference in plasma concentration for a 20kg child.

Are we accounting for that?

Jane Quitain

December 18, 2025 AT 17:54omg i never thought about this but now i’m terrified. i take my epilepsy med every day and i swear sometimes i feel like a zombie. maybe it’s the batch?? 😭

Nancy Carlsen

December 20, 2025 AT 00:05This gives me so much hope 🌱

Thank you for explaining it so clearly. I’m a mom of a kid on thyroid meds, and I’ve spent years second-guessing every change. Knowing the system is finally getting smarter? That’s the kind of progress we need. ❤️